The Cossack of Lugansk

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / The Cossack of LuganskThe Cossack of Lugansk

“Neither vocation, nor confession, nor the blood of forefathers makes a person belong to a people… He who thinks in a language belongs to its people...”

Vladimir Dal

From the editor: In the town of Lugansk, a small museum is devoted to the life and work of Vladimir Dal. In a sense, this museum is a reminder that the Russian world also consists of these half-forgotten corners and that its historical and cultural map is also made up of such inconspicuous details. Finding them and taking inventory, so to speak, is a job in itself.

At the end of the 18th century in a small village on the shores of the small Luhan creek in the southeast of Ukraine (Little Russia), a young Danish physician and his German wife settled. Soon after, they had a son, a person whom fate determined would become one of the greatest research linguists in the history of Russia. His works, which had great influence on the development of Russian literature and culture, bear the signature “The Cossack of Lugansk.” It was under this pseudonym that the great scholar, patriot and humanist, Vladimir Dal, achieved global fame.

Despite the fact that he lived there for only four years and left as a young child, Dal chose a nickname that would forever tie him to Lugansk. Perhaps this was a sign of his commitment and love for his homeland, a place that Dal carried through life and embodied in his work. The full extent of these sentiments finds expression in his life’s main work – the creation of the Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Russian Language.

In Dal’s hometown, they have not forgotten their famous son either. Today in Lugansk, the Dal Literature Museum exists as part of the city’s Museum of History and Culture.

The small building that houses the museum, which lies on a quiet street in the city’s historic district, could not agree more with its content and be better at immersing visitors in the atmosphere of the era. Books, photographs, portraits and everyday objects associated with Dal fill several rooms. Every room is a room in the museum, and each provides an insight into a certain stage of the distinguished scholar’s bright and meaningful life. Whether his study at the naval cadet corps in St. Petersburg, his service on the Black Sea Fleet and in the army, his work as a civil servant or his passion for the Russian language and literature, each part of the story tells of a person who was honest, persistent and, perhaps most importantly, completely enthralled by his work. Moving from one room to another, we learn how Dal’s youthful enthusiasm for literature and writing gradually transformed into a systematic and focused academic pursuit. The result, well known today, is a unique collection of valuable ethnographic material and a dictionary, which bring together not just a vast number of lexical units in all their various meanings, but preserves, as Dal said himself, “the spirit of language.” To this day, Dal’s dictionary remains an indispensable tool for everyone who in one way or another uses the Russian language. Indeed, it is quite difficult to find a dissertation today whose author does not in some way find it his duty to make reference to Dal’s dictionary. This is the case regardless of the area of study. In politics, medicine, geography and other areas, Dal gave new meaning to already familiar words and reported facts related to their origins.

A collection of rare books collected throughout the former Soviet Union serves as the basis for the museum’s exhibit. The old editions are impartial witnesses to their era and contain valuable material for any historian. For example, one part of the exhibit tells of Dal’s study at the naval cadet corps and displays a training manual called “Signals Used to Produce Tactical Movements of Row Fleet.” There is also an outline of a history on the naval cadet corps with a list of students over the previous 100 years, as well as Dal’s autobiography. The museum room that highlights Dal’s involvement as a doctor in the military campaign of 1829-1830 displays a set of medical instruments of the time, as well as a human anatomy atlas with explanations based on medical science as practiced in the first half of the 19th century.

Dal’s most significant work, the Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Russian Language, is naturally given a special place in the museum. Various editions of the famous dictionary have been collected and placed on display. The dictionary was originally published in brochure format, which Dal referred to as notebooks. A total of 21 such notebooks were published. They were subsequently reissued in a four-volume dictionary, the first of which was sent to Emperor Alexander II. Following its approval, work on the dictionary continued. The second edition, revised and updated, was published in 1880-1882 after the author’s death.

The museum also contains a full version of the publication prepared by Baudouin de Courtenay (1912), which became the basis for the version best known today. The real gem of the collection, however, is a rare piano, which, according to the family history, Dal’s mother loved to play.

A separate theme in the museum is an exhibit devoted to the contribution Dal made to Ukrainian language study. The “Cossack of Lugansk” originally paid great attention to studying the Ukrainian language and folklore. He also proved himself to be a talented translator from Ukrainian to Russian. Many of the Ukrainian words he gathered were subsequently incorporated into a dictionary of the Ukrainian language, which was compiled by Boris Grinchenko.

Despite the overall modesty of the museum’s exhibits, one cannot fail to recognize that its staff, with the help of patrons and sponsors, was able to gather several extremely rare and valuable artifacts for the collection. The Lugansk museum will be of great interest both to those who are being introduced for the first time to the life and work of the well-known linguist, as well as to professionals who have devoted considerable time to studying his heritage.

The special role the museum plays in the cultural life of modern Lugansk cannot be overlooked either. For two decades it has served as a platform for communication and a center for those captivated by literature and art. On Thursdays, Dal literary evenings are held at the museum, which bring together philologists, teachers, those involved in the world of art and anyone else who is interested.

“I loved my native land and gave to it as I was able,” is one of Dal’s most famous sayings. These words can rightly be considered his motto throughout life.

The son of a Dane and a German, born on the territory of modern Ukraine, Dal contributed to the development of Russian language studies in ways that cannot be overemphasized. And thereby the scholar presented his descendents with further evidence of the unique role and mission the Russian language has as a link between cultures and peoples.

New publications

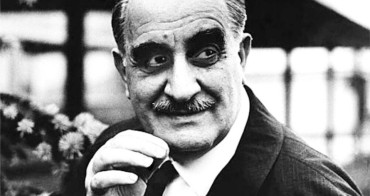

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

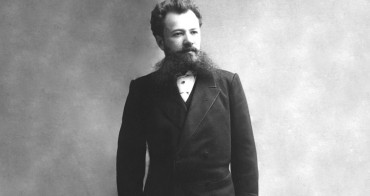

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

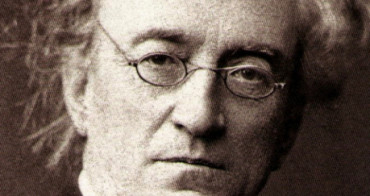

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...