Push&Go

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Push&GoPush&Go

There was a brief period in the history of the journal Ogonek when its publisher was Leonid Bershidsky, a well-known journalist who had achieved success in a number of formats. Bershidsky tried to reform Ogonek, reorienting it toward a younger and more successful readership (while the attempt was successful, it is not really possible to speak of the result: a few months after the reforms began, the journal’s investor changed his mind and brought back the previous editor-in-chief, Viktor Loshak). Among the many innovations that rapidly died out, it is worth remembering one in particular – a series of comics called Push&Go in which Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol together experience several adventures based on actual news from the time. Conservative readers complained, wondering what sort of theatre of the absurd they were witnessing. Upon his return, Loshak removed the comic strip, and no one seemed to care. Whether absurd, or, conversely, too logical, the connection between Pushkin and Gogol that the comic’s author had managed to catch is something that merits discussion during these days of Gogol’s birthday celebrations.

This is not the connection that literary critics and historians write about. Moreover, this story bears relation to neither the written works of Pushkin and Gogol nor to their lives. The only thing that matters are the dates of their birth and death. Pushkin was ten years older than Gogol. Gogol, in turn, outlived Pushkin by fifteen years. Periods of both ten and fifteen years provide ideal intervals for the same commemorations (both Soviet and post-Soviet readers have treated Pushkin and Gogol with similar reverence). This period is neither too short nor too long. Ten years does not allow the anniversaries to be merged into one, but it nevertheless does allow one to compare Pushkin’s and Gogol’s works and, more precisely, their respective celebrations, including the contexts in which they have taken place.

Under Stalin the anniversaries of both writers’ deaths were for some reason marked on a much larger scale. Pushkin’s 150th birthday in 1949 was quite unlike the memorial anniversaries in 1937 and 1952. These two years are so obvious that one need not even explain that they represent the peak of the terror and the last year of Stalin’s life. Perhaps the difference between Pushkin and Gogol in the most primitive retelling – it is silly to compare the tragedy of their two fates, but it is worth delicately pointing out that Pushkin did not burn the second volume of Dead Souls – is easily projected on the difference between the years 1937 and 1952. In 1937, Elena Bulgakova could naively, although honestly, take joy in the arrest of those who had tormented her husband. In 1937, the common man could consider Chkalov’s flight to be the event of the year. In 1952, however, any illusions on the part of the elite and the masses alike were safely in the past. Propaganda had gloomily cultivated the interwar mood, and there could be no hope for something good and bright in the near future. Andreievsky’s dismal Gogol, who stood at the start of Gogol Boulevard, had much more to say about 1952 than Tomsky’s Gogol. The monuments’ switching characterized that Kafkaesque time quite well. Monuments were also played with in 1937, but at least it was done with cynical wit: on the pedestal of the Pushkin monument the lines about the iron age and freedom were smashed off. The commemorations of 1937 could still be seen as a belated grande finale in the debate on the passage of modernity. In 1952, only the crazy could see the thaw already standing on the threshold.

* * *

In the 1990s, it seemed as if the tradition of popular celebration had been lost forever. The lost 50th anniversary of the Victory in the Great Patriotic War, commemorated in an almost make-believe manner in 1995, seemed like the most Russia was capable of in that mythologized decade. The 850th anniversary of Moscow’s founding, in which the grandiose Luzhkov style was crystallized, is best remembered for the unpleasant stampede at the Jean-Michel Jarre concert and the number “850” that had so obviously been overfed to Muscovites. At the time, nobody could have imagined that Pushkin’s 200th birthday could somehow be a success. But it was.

It is difficult to understand what exactly turned Pushkin’s anniversary into the celebration of the decade. It certainly wasn’t the renaming of the Rossiya movie theatre or the opening of the Pushkin restaurant. Most likely, as with many other phenomena in the 1990s, television played a key role. For several months in a row after the program Vremya, Channel 1 read Evegeny Onegin line by line while showing a clock counting down to Pushkin’s birthday. A humorous but deeply moving English version of Onegin came out, and Leonid Parfyonov, before he ever got involved with Newsweek or Namedny, presented NTV viewers the Living Pushkin series. Quite obviously, the country was experiencing catharsis. The secret of Pushkin’s victory over both state-sponsored and popular programing was in the general atmosphere that prevailed during the first half of 1999.

We still didn’t know that the 2000s were upon us, that a completely new life was emerging into which the repulsive 1990s were quietly fading. We didn’t know it, but we felt it. The feeling that a new life was upon us was everywhere, including in the political conflicts that nearly saw the parliament impeach Boris Yeltsin, in the international news that centered mostly on NATO’s bombardment of Yugoslavia, and even in Zemfira’s debut album whose songs could be heard through windows everywhere from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok. The feeling of weariness from the 1990s, new hopes, a new life that was destined to come – could Pushkin be superfluous in such an atmosphere?

Ten years have passed since then. Gogol was younger than Pushkin by ten years, and now we are celebrating Gogol’s 200th birthday.

In those days, when anniversaries of death were marked with more noise than birthdays, it was common to write about Pushkin as “the great poet” and about Gogol as “the great artist of the word.” The difference, just as now, was at the level of nuance. Then there was the British Onegin, frivolous and perhaps a bit absurd. Now we have the Russian version of Taras Bulba, heavy and ponderous with a clear patriotic message. The Gogol movie theatre no longer exists, but perhaps we don’t really need it any more. Instead, we have the Gogol restaurant and club, which over the last decade has become a fashionable if marginally Bohemian establishment in Moscow where 35-year old intellectuals spend their evenings drinking. These are the people who perhaps more emotionally and more actively than others experienced the hopes of 1999, only to realize later that there would never be room for them to dine at the ultra-glamorous Pushkin restaurant.

The context, both political and informational, is also similar, but also with nuances. That something is over and that something is beginning – that is certain, unlike the hopes, the emotional ascent, and even Zemfira’s songs playing through all those windows. Zemfira, together with Oleg Tabakov, performs as the reader in Parfyonov’s new film on Gogol. Parfyonov, as in the film about Pushkin, walks along Nevsky Prospekt. The ease of his gate, however, has somehow disappeared.

The thought arises that we should in fact celebrate the 200th birthday of Pushkin once again. After all, he did not burn the second volume of Dead Souls.

New publications

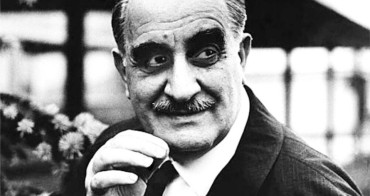

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

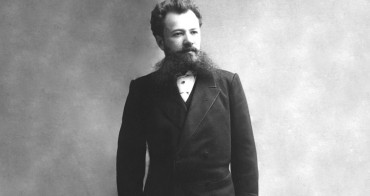

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

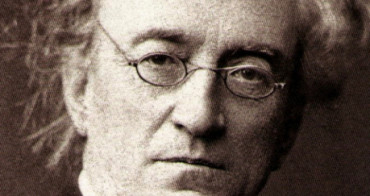

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...