Max Voloshin: The Last Cimmerian

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Max Voloshin: The Last CimmerianMax Voloshin: The Last Cimmerian

Marina Bogdanova

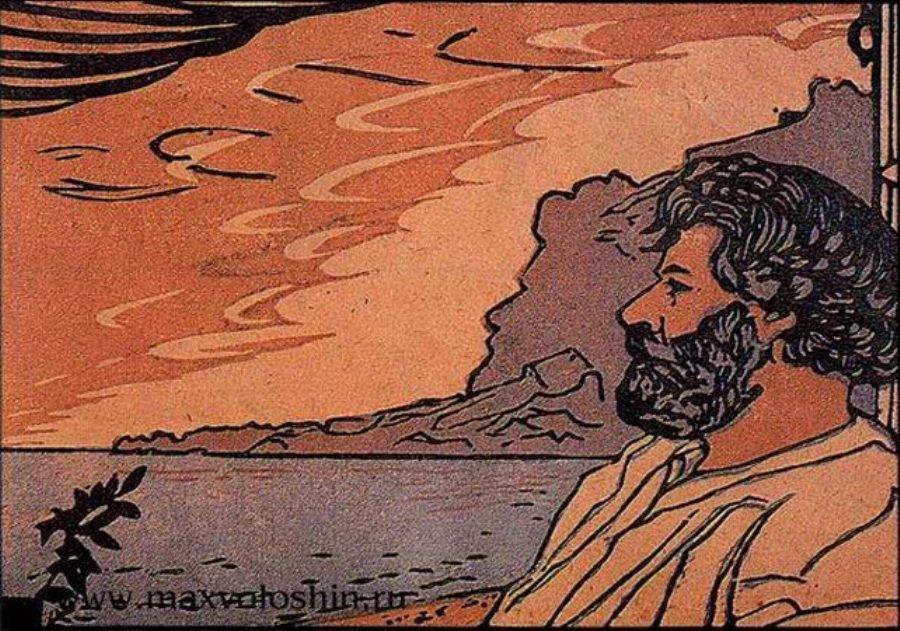

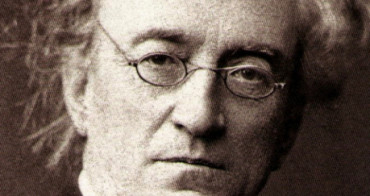

Maximilian Alexandrovich Voloshin

Portrait by K. Kostenok. Leningrad, 1925

Among the many geniuses of the Russian Silver Age, the name Maximilian Voloshin can sometimes be overlooked. His verses are not quoted all that frequently, and his aquarelles, though recognized, are not widely reproduced for sale. Likely enough, an average Russian might only remember Voloshin’s association with the Crimean town of Koktebel and a certain photograph of a heavy, disheveled Max in a chiton with his head bandaged. Or even more likely, they would only remember his name: “Sure, there was such a poet at the beginning of the 20th century…”

Contemporaries responded to Voloshin more often with irony than seriousness. Mandelstam openly judged him to be a bad poet, Gorky thought he was a terrible bore, and the satirist Sasha Chorny awarded him the acerbic nickname “Vax Kaloshin” (suggesting a polished overshoe), which really stuck to him. Even Max himself admitted: “Everywhere I go, especially among literary types, I sense myself to be a beast among men—something out of place.” But the more time passes, the better we can perceive this eccentric from Koktebel, this Cimmerian, this clever young man—Max Voloshin.

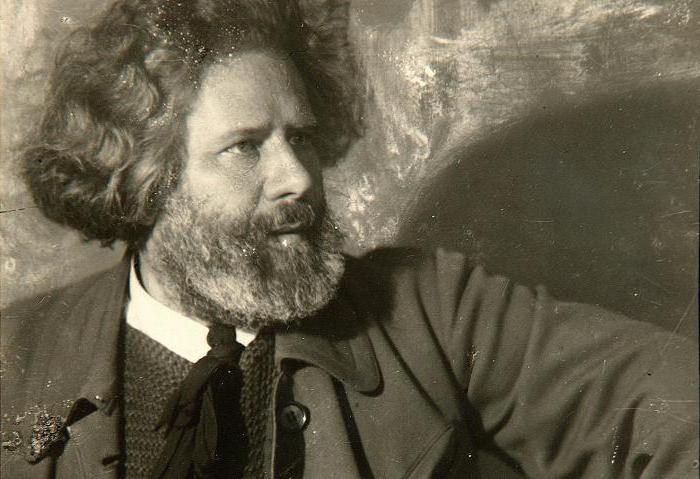

Max Voloshin

“To Walk Across the Whole World With Burning Steps”

He was born in Kiev. His father, Alexander Maximovich Kirienko-Voloshin was descended from Cossacks. His mother, Elena Ottobaldovna (née Glazer), was descended from Russified Germans and had a strong, unconventional personality. She left her husband when Max was only two years old, practically breaking off all relations with her husband (who died soon after). She did not remarry, as she preferred to live independently, raising her son without the help of the Kirenko-Voloshin family. Little Max first lived with her mother in Sevastopol, and then they moved to Moscow. In Moscow, the boy entered a preparatory school, but he did so poorly there that when he later transferred to another school in the Crimean town of Feodosia, this school’s “elderly and compassionate” director, after reading his previous teachers’ comments, “raised his hands in dismay and said, ‘Miss, of course, we will accept your son, but I should warn you that we cannot fix an idiot.’” Nevertheless, Max became a popular sight in Feodosia: this adolescent who loved literature, wrote verse, and took up everything from theater to painting was seen as a star—they even called him a “future Pushkin.”

Elena Ottobaldovna’s idea to leave the bustle of Moscow and move to the Crimea turned out to be truly fortunate. Life in Moscow kept getting more expensive, their affairs weren’t going very well, and her son was developing asthma—but there just happened to be large estates for sale at low prices in the tiny town of Koktebel in the Crimea. To Max’s great happiness, he and his mother moved to the Crimea, and this was a fateful decision. His youthful love for the sea, sunlight, ancient mountains, and the peculiar weather of the Crimea would stay with him until his death. The Crimea gradually became fashionable, as summer vacationers came there (interesting, creative people among them). Not only was the famous painter Ivan Aivazovsky a trustee at Max’s preparatory school, but he also responded to this beginning artist’s aquarelles with great approval.

Returning to Moscow as a law student, Max Voloshin didn’t lose his anarchist tendencies and goodhearted love of freedom, even in the capital. So, when the student protests began, big, curly-headed Max turned up in the very center of the student rebellion and was arrested for taking part in the disorder. He was sent back to Feodosia under police supervision and banned from the university.

The next stage of his life involved travels in Europe, laying a line for the Tashkent-Orenburg Railroad, an infatuation with Nietzsche, working for journals, Paris, Italy, Spain—new friendships, new impressions, new poems. This shortish, overweight student in a pince-nez was a hopeless eccentric, passionately in love with art and travel. He was constantly getting into trouble, but he was invariably kind and magnanimous. He managed to meet and befriend the leading figures of his time—from Picasso, Verhaeren, and Rodin to Bely, Ivanov, and Balmont. He lived as befitted a bohemian, without a cent to spare and shocking the common people with his appearance. He wore a cape, a top hat, wide velvet pants similar to those worn by workers, and strange vests and blouses. He was at home in Montmartre, but simple people tried to keep their distance from this “charlatan and mesmerist.” His nickname among the French was Monsieur C’est trés intéressant! (Mr. “Very Interesting!”), or Max de Koktebel.

Meanwhile, those who spent time with this “Russian eccentric” didn’t regret their decision. The Polish translator and playwright Wacław Rogowicz remembered his meetings with Max de Koktebel: “Max was everywhere, saw everything, introduced people, organized, served tea or grog—finally, having assured himself that everyone was feeling good, he would take several close friends to one side and sit them down to try a special drink: red wine mixed with…myrrh.” Max was interested in everything: he underwent a Masonic initiation, took up Buddhism, and discovered Rudolph Steiner’s anthroposophy.

The poet Andrei Bely wrote: “Moscow needed Voloshin in those years: without him, a person who could soften the sharp corners, I don’t know where our differences of opinion may have led us… he was like a poster with a picture of the ‘angel of peace’…”

“I Hear with Your Ears, I See with Your Eyes”

Margarita Sabashnikova

The year 1903 was a fateful one for Max. He met Margarita Sabashnikova, an artist with the features of an ancient Egyptian queen. Meanwhile in Koktebel, construction went at full speed on the house that would become legendary. Margarita came to Paris to study. In Russia, she took classes with the famous artist Ilya Repin, who thought she was quite talented. Max was enchanted by her, nearly from their first encounter.

The silly poet dragged his beloved to all the Paris museums. They drew and talked about everything together. Gradually, Max understood that he was encountering fate. But Margarita was in no rush to reciprocate his emotions—her heart didn’t belong to anyone, as, entirely in keeping with the fashion of the Silver Age, she felt herself to be “dead and alabaster.” Her coldness drove Voloshin to despair, and he kept losing and regaining hope until he finally succeeded: they were married and went on an absurd honeymoon along the Dunai.

This marriage didn’t last long. The young couple settled in Petersburg and soon moved in with the prominent poet Vyacheslav Ivanov, whose apartment attracted bohemians from both Russian capitals. As might be expected, Ivanov and Margarita fell in love with each other. A distraught Margarita came to Ivanov’s wife, Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal, to apologize and bid farewell, but Zinovieva-Annibal told her that she didn’t need to leave, as she had already become a very important person to both of them. Lydia had so thoroughly joined together with her husband that she was prepared for an open relationship and even suggested a three-way bond as the highest and fullest form of Eros and esoteric revelation.

Of course, this didn’t leave any room for Max, but he sincerely loved Margarita and admired Ivanov, so he gave her full freedom in the matter. Meanwhile, their daily lives went on as before with Voloshin and Ivanov working on shared projects and both families (or were they essentially one family?) living together. This situation was torment for all of them and came to a dramatic conclusion. Margarita felt compelled to write to her parents explaining the change in her family circumstances, and her mother declared that Margarita would live with the Ivanovs’ over her dead body. As a result, Max returned to Koktebel with his mother, leaving behind this “circle of people who specialized in psychological and sexual experiments.” Margarita’s family placed her in a sanatorium. The Voloshins’ marriage, which was already on thin ice, had effectively come to an end, but Margarita and Max managed to remain friends.

Cimmerian Twilight

Left on his own, Max completely immersed himself in poetry, philosophy, and his attempts to understand the world he lived in. His collection poetry Cimmerian Twilight is a new act of reclaiming the ancient earth, the eternal sea, the hills, wasps, cicadas, and stars. The barren and gloomy winter in Koktebel became for him a universe that needed to be discovered anew and praised. It’s no accident that Voloshin wrote so many hymns addressed to antiquity during this period: the wild natural surroundings of the Crimea—which at that time still had not become a crowded resort destination—disposed one to an almost devotional state of mind.

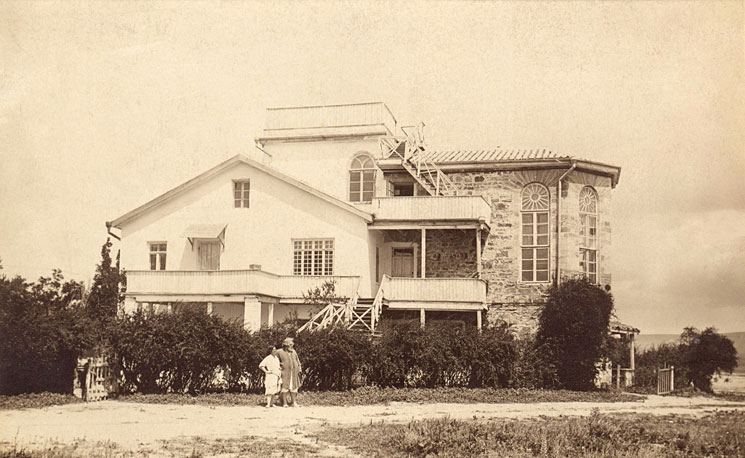

Time passed, his work continued, new verses brimmed with a new fire—and Max’s house was built, a house to which he could invite his friends, a place where he could talk with them about anything and once again live, make jokes, and rejoice. This house had a landing for stargazing and a great number of small rooms. It was finished with crude stone and looked a little like a tower and a little like a boat. Max designed it himself. Here, far away from the nervous enticements of Petersburg, far from the narcotic revelations and strange, distorted desires of the decadent world, Voloshin even changed in appearance. He walked around in loose chiton, crowned with a wreath of wormwood. (Locals asked him to wear pants under the chiton so as not to embarrass the women.) He swam in the painfully cold water at the end of March, wandered in the mountains, taking only a staff with him, and felt like the owner of this dry and beautiful land of Cimmeria.

Aquarelle by M. Voloshin

Voloshin didn’t just praise his land in hymns—he also drew it. The artist and great expert in art Alexandre Benois judged that Voloshin’s aquarelles represented “not the Crimea that any camera can shoot but…some kind of idealized, synthetic Crimea.” The landscapes of Feodosia blended with memories of Spain, Hellas, and Thebaid. It wasn’t the Crimea but a dream of the Crimea.

He continued to visit Moscow and Petersburg, even showing up at Ivanov’s apartment, and kept up various literary activities. He was a great lover of mystifications and getting on people’s nerves. But his most famous mystification was done for a reason other than spiteful amusement.

Cherubina de Gabriak

In 1909, two young and very talented poets came to visit the Voloshins in Koktebel: Nikolai Gumilev and Elizaveta Dmitrieva. These young people had met at the Sorbonne, where Dmitrieva took a course in Old French Literature (having previously attended courses in medieval French and Spanish literature at Petersburg University). Gumilev was more than a little enamored with his traveling companion, but she preferred Max. Gumilev was forced to leave Koktebel alone and extraordinarily vexed.

Dmitrieva completely enchanted Voloshin. He even proposed to her, only to be turned down. But here began one of the most exciting schemes of the Silver Age.

Dmitrieva had had a terrible childhood. She was bed-ridden with tuberculosis, which had left her with a limp, one of her mother’s friends had raped her as an adolescent, her brother was a drug addict and out of his mind, and her sister had died in childbirth. Hardly anyone noticed or wanted to know this unattractive young translator.

But soon the Moscow journal Apollo (where Voloshin worked) received poems from a mysterious aristocratic beauty. The letter was scented with subtle perfumes, and the verses, stylized after Old French poetry, were irreproachable. The letter was signed “Cherubina de Gabriak.” Of course, no one in Moscow knew that Gabriak was the name of a silly little wooden devil that stood on a shelf in Max’s home in Koktebel.

Elizaveta Dmitrieva (Cherubina de Gabriak)

The editor Sergei Makovsky, who had once rejected the “unphotogenic” Dmitrieva as a possible coworker, was wildly ecstatic and demanded more poems—as many as he could get! Other details from the biography of this mysterious Cherubina gradually came to light: it turned out that she was an ardent Catholic and even dreamed of joining a monastery. Makovsky fell madly in love with this fascinating unknown woman and tried to spy on her to achieve at least some kind of “devirtualization.” Sometimes Cherubina would talk with him on the phone, and her melodic, jesting voice drove the poor editor completely out of his mind. All Petersburg was talking about this mysterious Spanish woman, and she was the number one riddle in literary circles. The intrigue lasted for a month and ended in a terrible scandal. Lilia incautiously admitted her role to someone, who gossiped to someone else, and finally Makovsky found out that all this time an ordinary teacher was hiding under the romantic mask of an aristocrat. Makovsky met Lidia once more and was terribly disillusioned. The editor took back all the amorous vows and passionate speeches addressed to the beautiful Cherubina. Her last selection of poems came out under the name Dmitrieva, and her work with Apollo ended there.

The worst part was Gumilev’s behavior. After making another proposal to Dmitrieva and once more being rejected, he insulted her in public. Voloshin slapped him for this. They challenged each other to a duel, and the two poets exchanged shots at Chernaya River. Old dueling pistols were acquired and seconds were appointed. Gumilev’s car broke down on the way, the pistols froze, and Voloshin’s second, Znosko-Borovsky lost his boot in a snow bank. Gumilev insisted on a duel to the death and suggested a distance of five paces, but the seconds strongly opposed and they exchanged shots from 25 paces. Gumilev missed. Voloshin shot into the air. The lost boot was found by the police and became evidence that led to both duelists being arrested. This duel came to be mocked in all the literary salons of Moscow and Petersburg.

After suddenly finding herself in the epicenter of such a powerful scandal, Elizaveta Dmitrieva couldn’t handle it. For four years she stayed quiet as a poet (though no one had objected to her verses) and broke all connection to literary society. She married a childhood friend, changed her last name, and left Petersburg.

Life at Koktebel

But all this happened in Moscow and Petersburg. In Koktebel, the waves plashed and guests arrived for the beginning of the season. Voloshin made up a special reminder: “I recommend you bring with you hay sacks and dinnerware (including a plate), and a basin, if you need one. There will be a table set at the dacha (about a ruble for a dinner); the rooms are free. There are no servants. You can carry water yourselves. This isn’t a resort. It is a free community of friends, where each person who “shows up” will become a full member. For this to happen, one must have a joyful attitude toward life, love for people, and a willingness to do one’s part for our intellectual life.”

Voloshin’s House in Koktebel

Beginning in 1911, this house endured a downright invasion every summer: poets, artists, actors, actresses—just about everyone was there. They all made up a cheerful tribe of “goofs.” These goofs had their own rules: there was as much cheerful play and joyous energy as possible. They dressed as simply as Max and Elena Ottobaldovna, wearing chirons and loose-fitting Tatar pants. The ladies ran around with uncovered heads, either barefooted or wearing the simplest shoes (which scandalized the more proper vacationers staying nearby).

The purest happiness reigned among them. They all teased each other, but in good fun, and there was also space to work without obstacle. It’s hard to imagine how many masterpieces were created in this house! Concerts, plays, swimming, trips to the mountains, and group revelries—these are the activities to which the summer days and nights at Koktebel were devoted.

Max and his guests (staged photograph)

Max’s “tribe” expanded every year. The neighbors gnashed their teeth upon seeing these strangely dressed (or completely undressed) visitors and tried, unsuccessfully, to keep them under control. During the difficult period of the 1920s local peasants openly despised Voloshin, thinking that he was undercutting their business. They would rent out huts and barns, while Max would open his two-story house to all takers totally for free, as long as they were good people.

The Poet in Times of War

In 1905 Max was a witness to Bloody Sunday. After his Parisian bohemian life full of coffeehouses, exhibitions, conversations about the eternal and poetry readings, he suddenly found himself in hell. Bodies were carried past him from Troitsky Bridge—men, women, and a smartly dressed dead little girl that would be seared on his mind. He spoke with eyewitnesses, questioned reporters he knew, and threw himself into newspaper editing. He wrote everything he saw and heard in detail in his diary. The disorder continued the next day, and Voloshin saw the “Cossacks’ attack” on the crowd with his own eyes.

When the Revolution began, Max was in Koktebel. He formulated his position as precisely as can be: however naïve it may sound, he decided to remain “above the battle.” Too much murk had been kicked up. It impossible to define which side he was on because either side had its own reasons and strengths, and each also had its share of dirt and blood. He lived in Koktebel and welcomed friends from either side into his house. He refused to choose between them.

This didn’t stop him from interceding for Red Soldiers when the White Army was in the Crimea, using all of his influence and reputation to do so. Sometimes, his intercession out of respect for a famous poet would save the person. One time, he defended the poet Mandelstam—although there was a disagreement between them, and Voloshin’s defense of the poet was quite peculiar, as he argued that Mandelstam couldn’t be serving the Bolsheviks because he “is not fit for any kind of service, or for political convictions either: this not something he’s ever suffered from.” Mandelstam was released.

During this time, Voloshin also described honestly and truthfully everything he saw. Subsequently, his poems about the Red Terror would be unconditionally banned in the USSR: From an ideological point of view, the Great Revolution was led by angels and saints, and all blood and horror needed to be ascribed to the White Army. In addition, Voloshin did everything he could: he gave lectures, chaired a Commission for improving the situation of scholars in the Crimea, and distributed academic rations.

Monument to Voloshin in Koktebel

After the end of the Civil War, Voloshin remained the very same Max from Koktebel. His friends still came to visit him. In 1923, Max’s mother passed away, and he married Mariia Zabolotsky — who wasn’t an artist or a poet, but simply a kind and sympathetic woman who selflessly helped him take care of his dying mother.

More than anything, Max wanted for his house to pass into the possession of the state so that even after his death his friends could gather there. In 1929 Maximilian Voloshin suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and on 11 August 1932 he died. Before his death, Max gave his house to the Soviet Writers’ Union. According to his will, his widow, Mariia Stepanovna, became the custodian of the house, and she kept it just the way it was during his lifetime. Max was buried at the top of Kuchuk-Enishar Mountain, from which all of Koktebel is visible. The flat marker on Voloshin’s grave has become a site of pilgrimage. Even now, residents of Koktebel see lion-headed Max as something like their mystical guardian and defender. The Cimmerian poet became a deity to those places he loved, whose praise he sang.

New publications

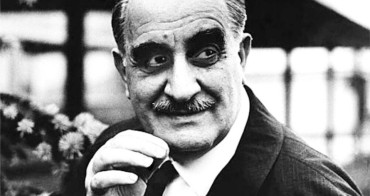

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...