Aleksei Rodzianko. Maintaining a Connection to Russia

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Aleksei Rodzianko. Maintaining a Connection to RussiaAleksei Rodzianko. Maintaining a Connection to Russia

Julia Goriacheva

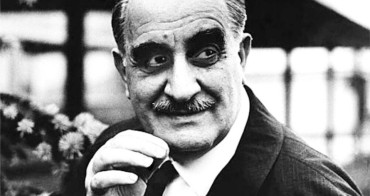

Aleksei Rodzianko is the director of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia and the great-grandson of the last Chairman of the tsarist State Duma, Mikhail Rodzianko. We spoke with him about what happened with his family after their exile from Russia, the Russian émigré community in America, and Russo-American relations.

Photo: RIA News Agency

– Mr. Rodzianko, we are meeting on the cusp of the century anniversary of the revolution, which is also the century anniversary of the emigration. Please remind our readers how your family ended up in the USA.

– In 1920, at the end of the Russian Civil War, when it was clear that the Red Army would win, my great-grandfather, grandfather, and my father’s brother and sister all emigrated out of Novorossiysk on an English steamer. And they ended up in Serbia, since my great-grandfather, Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko—who was the last Chairman of the State Duma of tsarist Russia—decided to live in an Eastern Orthodox country. My grandfather, Mikhail Mikhailovich, also remained there. And my father was born in 1923 in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Incidentally, my grandfather, going against family tradition, studied at the agro-technical university in Moscow. All of his cousins and forebears studied in the Page Corps. But he took up managing his father’s estates. These estates were in the north (near Novgorod) and in the south of the country (near Ekaterinoslav, which is now called Dnepro). As it happened, when the revolution occurred, my grandfather was managing an estate down there, which he needed to abandon in 1918 due to the disorder. At first, he made it to Novomoskovsk, and then further behind the lines of the White Army.

In the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, my grandfather continued his former occupation, now managing the estate of a Hungarian landowner. My great-grandfather also lived there with his wife. He died of a heart attack in 1924, three days after Lenin died. At the time, this was even in the newspapers. When the Red Army started to approach during the Second World War, my grandfather and his family left for the West. Their acquaintance, Vladimir Petrovich Popovsky, a Russian landowner from Romania, traveled through Serbia with his cart and horses. It was he who drove them to Munich on this cart. There, in 1949, my father married Tatyana Alekseevna Lopukhina, who had arrived from Russia via the Baltic region. My paternal and maternal grandmothers were already acquainted from life in Petersburg. And my parents arrived in America at the end of 1949.

– I read that the Tolstoy Foundation helped your parents move and start their lives in the USA.

– My father’s sister traveled on that same cart that carried my grandmother and grandfather. She married Leo Tolstoy’s grandson Vladimir. They traveled to the USA together. Meanwhile, Alexandra Lvovna Tolstaya, the writer’s daughter, had organized a foundation a little earlier (1939) with the purpose of helping refugees and displaced persons. Her right hand was Tatyana Alexeevna Shaufus, a nurse and social activist, who would later become the president of the Tolstoy Foundation. Another assistant there was Ksenia Andreevna Rodzianko, our distant relation. They helped my parents move to the USA. They helped a lot of Russians. At first, my parents relocated to New York, the Bronx, but then we moved to the suburbs and lived two kilometers from the Tolstoy farm and the Foundation’s New York office. And to this day my mother lives in the house that she bought with my father in 1956.

– Evgeny Alexandrov mentions in his book Russians in North America that Oleg Mikhailovich Rodzianko, your father, worked at a factory. Was this the well-known Bakhmetev match factory?

– Precisely. The match factory. Bakhmetev, the last ambassador of the Russian Empire knew my great-grandfather. Boris Alexandrovich Bakhmetev was a well-known engineer. While he was still in Russia, he designed and built a hydroelectric station in my great-grandfather’s estate, in a town near Novgorod called Toporok, to serve the family lumber business. Later, as is well known, Bakhmetev was sent to the USA as an Ambassador for the Provisional Government; he stayed in America after the revolution and took upon himself the concerns of Russian emigrants. Many emigrants from Russia worked at the match factory he founded. Bakhmetev was an unusual innovator. He was the first to think of placing advertisements on matchboxes. This turned out to be the hit of the season, and his factory flourished. My father’s first job in the USA was with Bakhmetev at that very factory. He worked in the afternoons and studied in the evenings…

– And he achieved significant success in his studies. It’s widely known that he eventually earned the title of a master of engineering at the Stevens Institute of Technology. In addition to working as an engineer at prestigious American companies and teaching at universities in New York, he also engaged in social activism within the Russian community. And in Nyack, NY, he was an active participant in the construction of the Holy Virgin Protection Church, as well as the church hall and the Russian Orthodox school.

– Yes, that was all so. I remember both the building of this church (in the mid-1950s) and the school building they built nearby in the 1980s: they bought the neighboring houses and built it on those lots. I remember “helping” in the construction as a little boy. My father was the foreman.

– Like your mother, Tatyana Alexeevna Rodzianko-Lopukhina, you also taught at the church parish school.

– Yes, I taught our own children and those of our classmates. History and Russian language.

– As someone who has taught Russian history, and as a great-grandson of Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko, can you comment on the recent words of Metropolitan Ilarion (Alfeev) to the effect that a monarchy enjoys certain advantages over other forms of government? Have you contemplated this?

– Yes, of course. Most likely, in comparison to what happened later in Russia, monarchy absolutely was superior. As for the question of whether this is an absolutely perfect form of government, I am more on the side of my great-grandfather: a limited form is better. Because a game with rules is always better than a game without rules.

Mikhail Rodzianko, 1910. Photo: ru.wikipedia.org

– The influence of your great-grandfather’s name (that of the last Chairman of the tsarist State Duma) probably made you more highly esteemed among both White émigrés and representatives of the American establishment with whom you’ve met?

– Of course, I noticed people’s interest in him and our family from an early year. He influenced my development, as did all my ancestors. You know what they all did, and that makes you feel responsible to them.

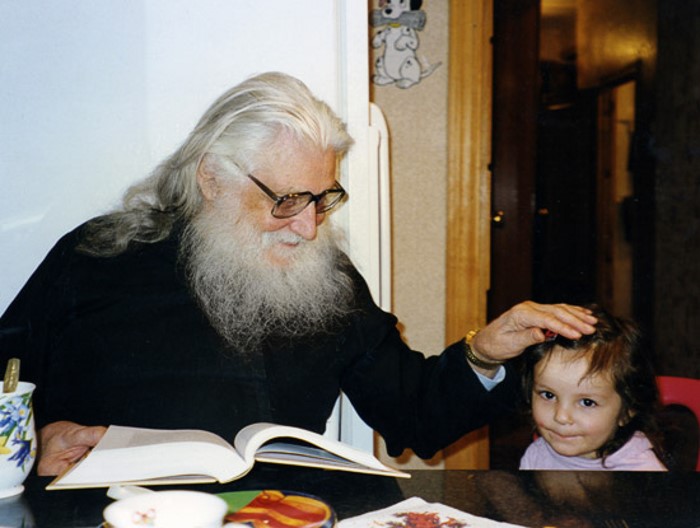

– What influence did the bishop Vasily Rodzianko have on you?

– That is my father’s older brother, and I can remember him since childhood. He lived in England for a time and from the late 1950s through the mid-1970s he hosted religious programs on the BBC.

I loved father Vladimir (as was his lay name). Tall and good-looking, bishop Vasily looks like someone Hollywood would cast as a bishop. It was always interesting to see him. Starting in the mid-1990s, he came to Russia quite often and lived here for some time. We always got along together very well.

Bishop Vasily (Rodzianko). Photo: stsl.ru

– For several years you have been a member of the Congress of Russian Americans (CRA). Please tell us about your work with them.

– This is a social organization that brings together American citizens of Russian descent. It was founded in 1973. In particular, we spoke out against the people conflating the concepts of Russia and Communism. Such simplifications were made as an aid to people’s comprehension and a means of raising a military spirit. But for us it was very important to see the differences. And the first person who was very successful at utilizing this understanding was Reagan. He understood that there was a significance difference, and there was no reason to antagonize the people—the issue was not with them but with the ideology.

See also: “Making the Russian Presence in America More Visible”

– The educational and charitable organization linked to your family have enabled American citizens of Russian descent to preserve their Russian identity. Let’s also consider the American Russian Aid Organization Otrada, where your parents worked as activists. Please tell us more about it.

Otrada was organized in the mid-1960s. At that time, my father and his Russian friends thought it would be possible to found a social and cultural organization. They bought a very nice plot of land relatively close to New York, where a camp for children had stood. And they built a Russian center there, where they showed Russian films, gave concerts, and organized holiday celebrations and various receptions. For several years, I participated in running the Otrada children’s camp there, which was for children, including me, who were not old enough for the Boy or Girl Scouts.

– You are the head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia. And you are leading it during a rather complex time. How have you been responding to the challenges of this moment, as both a Russian American and the head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia?

– All of my experience being Russian, growing up in America during the Cold War, and combining these things as smoothly as possible—this is a very useful background. The situation now resembles what was happening back then in many respects, though at times it seems that everything is upside down. Because, as I remember, back then left-leaning politicians and Democrats were favorably inclined towards the Soviet Union. And the right-leaning Republicans were always very strongly against it. Many people, including myself, a an American of Russian descent from the White emigration, most likely shared an understanding that the Bolsheviks and Communism were a certain evil that had brought many misfortunes to the Russian people (which included me) and that it needed to be fought.

But now, it’s completely the opposite: those on the right are more inclined to find common areas of interest and cooperation. Therefore, in some ways these are very similar situations, in some ways totally different. But I have experience in bringing together these varying interests.

– Who played a role in forming your character?

– To a certain degree, everyone I’ve come into contact with. As an example: I studied in the late 1950s and early 1960s at an ordinary American school, even worse than average, as Rockland Lake (the city where we lived) was very poor. Earlier, this was a place where the residents cut up the ice from the lake and sent it down the Hudson River to hotels in New York. Then, refrigerators and freezers were invented. And now this became a suburb of New York, where there were trains and bridges. And then, this town died, and there wasn’t anything to do. More than half the population received some form of social aid. At the time, I got to meet some of the most typical Americans, many of whom, incidentally, still had Dutch names. Because New York was previously called New Amsterdam, and before the English came it was a Dutch colony. My peers really liked teasing my older brother; they gave me less of a hard time. They called him Khrushchev.And that was the worst nickname possible. In 1973 I enrolled in one of the best universities in America, Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, and I was the only Russian (and only person descended from Russian aristocrats). In college, people understood this a little and understood whom they were dealing with. What’s more, the left opposition to the war in Vietnam was very strong. At that time, they mostly treated me like a celebrity. At the university, I started reading Russian literature and kept going to a course on Russian history. I was very interested. And I thought about a career in that field. Then, the Thaw started and translators were needed to accompany the delegations. I entered a competition and got work.

– In the State Department?

– Working for the State Department. I was on an independent contract: when I worked, I got paid, when I didn’t work, I didn’t. And in three years, from 1973 to 1976, I traveled to thirty-eight of fifty American states with various delegations. And I was in the Soviet Union about eight times. And then, at the beginning of 1977, they called me in for testing because they needed translators for talks about limiting strategic arms (SALT II). And I ended up on a government delegation. For about two years I lived in Switzerland where the talks were being held. I soon recognized that I needed to develop further. During my work trips around the states I learned about all the best business schools in the USA, about MBA programs; I enrolled at the Columbia University Business School and completed my studies on my savings. After that, I worked for a little over 30 years in the banking sphere. Fifteen of those years were in Russia…

– And as the head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia, how do you evaluate the current situation in the sphere of economic and trade relations between Russia and the USA? What paths do you see to overcoming the difficulties that have arisen?

– Firstly, things aren’t that bad. American companies operate successfully in Russia as before. So the first priority is to try not to cause any harm. Secondly, we need to hope that our diplomats are still able to improve relations between our countries. And thirdly, quite a lot depends on the climate for investment in Russia, which is primarily shaped by the decisions of the Russian government.

– I must ask a question about your hobby. For a significant portion of the time you’ve spent in Russia, you’ve been connected to polo. You chair the Russian Horse Polo Federation and own a Moscow polo club. As far as I understand, this isn’t simply a hobby that has become a business but also a show of respect to the traditions of your ancestors. After all, the Beloselsky-Belozersky clan, to which you belong on your mother’s side, were the founders and owners of a polo club in Saint-Petersburg. Isn’t that so?

– But I found out about that after I founded the club. Maybe that information was in my subconscious. I got into polo thanks to my daughter: she took riding classes in Bitsa. At first, I simply watched, but then I got in the saddle myself. And at the same time an acquaintance from back in New York approached me. He was founding a polo club in Russia and he wanted me to help as a sponsor. At the time I was the head of Deutsche Bank in Russia. A year later I bought the club. I always liked horses. And my younger son, Misha, also really enjoyed them. Now he is 29 and runs the club.

At the Moscow Polo Club. Photo: vm.ru

…I didn’t know that the Beloselsky-Belozersky family were my ancestors until my younger sister Tanya got a call from a museum in Petersburg. The caller said: “I’m standing here looking at your portrait.” This was a portrait of Princess Olga Esperovna Beloselsky-Belozersky, who later married Shuvalov, done by the German artist Winterhalter. We were interested and later learned that her daughter was the grandmother of my mother. The Beloselsky-Belozersky family controlled Krestovsky Island and founded three sport clubs: yachting, tennis, and polo. Diplomats and prominent Russian of the time played sports there, including polo. There are horses there to this day, and they are available for rent. The tennis courts also continue to operate. But the field where they used to play polo has now been broken into three athletic fields.

– You mentioned your children. You were one of five children yourself. You have six. You are Russian, and also American. How do you raise your children in a multilingual environment?

– My wife and I decided to speak Russian at home so that our children would speak Russian. And they do.

– Do your children attend the Russian Orthodox Church?

– Yes.

– Your family has always been active in the Russian community. In relation to this, I wanted to ask: Does a group of emigrants lose something by rejecting national and religious self-determination.

– My experience suggests that those who lose their religious identity very quickly lose their cultural connection as well.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...