Elena Pletnyova

On the first day of February, an event dedicated to the world of Soviet children's books was held at the International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam). It was moderated by Ellen Rutten, a specialist in Slavic studies from the University of Amsterdam. Historians, illustrators and collectors of Soviet children's literature, as well as translators of Russian literature shared about the history of children's books, starting with the post-revolutionary times.

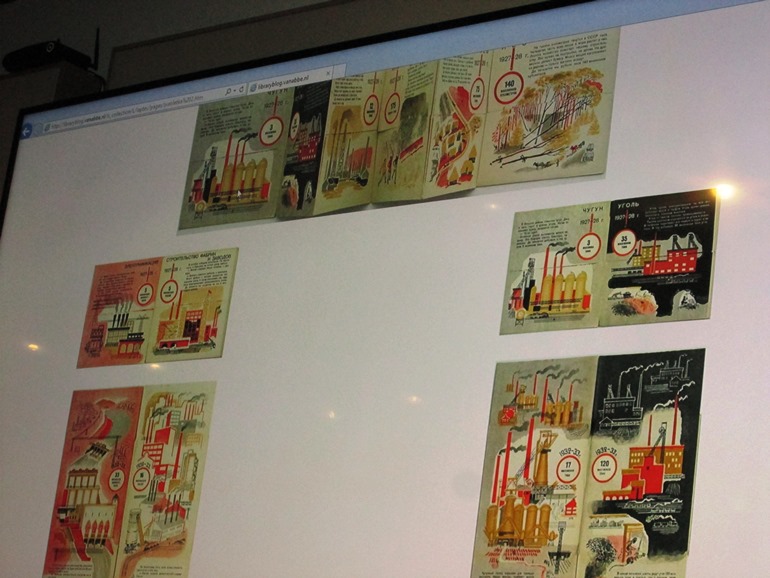

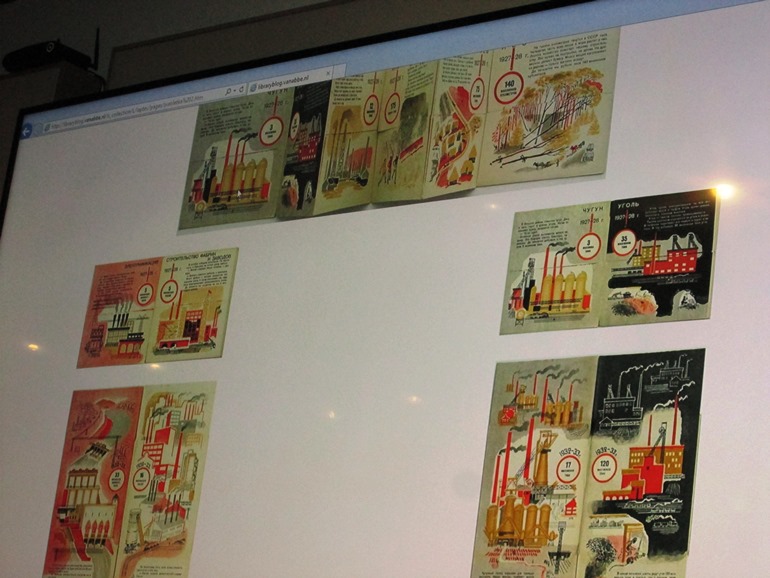

The Soviet children's literature has been examined in Netherlands from various aspects. They take in consideration ideological point of view and development of drawing, and use them to study even the labour movement, which the Soviet Union used to lead since 1917. In the 1920s, the USSR published books on industrial processes, for example, How cotton turned into chintz, How beet root turned into sugar, Bread-baking plant, Wood, At the brick factory. Children had to be raised into conscientious workers.

Albert Lemmens and Serge Stommels, researchers and collectors of children's books, presented digitized books with illustrations by Olga Deineko. She was a famous Soviet artist, a student of Vladimir Favorsky, and a member of the Revolutionary Poster Association. Her range of works included those about pioneers’ life and portraits. She became famous as an illustrator of children's books. Together with her husband, Nikolai Troshin, the artist created a large series of children's books on industrial topics, which helped a whole generation of Soviet citizens to grow up. Hays Kessler, an employee of the Institute of Social History, shared that he studied industrial processes in the USSR of the 1920s using those illustrations.

Albert Lemmens described the changes in graphics style from Russian Art Nouveau at the end of the XIX century, which was represented by Elena Polenova and Ivan Bilibin, to the avant-garde and even abstract drawing of Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky (by the way, it was not appreciated by any children of any generation), which in turn, was replaced by socialist realism, proclaimed by Maxim Gorky at the 1st Congress of Soviet Writers (1934).

Many children's books on defense of the country were written and published in the USSR in the second half of the 1930s. At that time, Alexey Pakhomov, an illustrator, became very well known in this field. He was a student of Vladimir Lebedev, who headed the Children's Literature Publishing House in the late 1920s. Pakhomov started with pencil drawings for children's books and quickly turned into one of the best artists in the area of children's book graphics in Leningrad in the period from 1920s to 1940s. He successfully collaborated with such popular children's magazines as "Chizh" and "Ezh"; their issues have been carefully kept at the Institute of Social History.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the style of children's graphics changed again. It became more of ethnic type. That was the time, when Yevgeny Rachev, an illustrator and animal painter, became famous. He worked for publishing houses since the 1930s and became the chief artist of the Detsky Mir Publishing House in 1960 (it was renamed into the Malysh Publishing House in 1963). Striving for psychological expressiveness and social acuteness of images, the artist used subtle natural qualities, habits and behaviour of animals that he observed. Picturing them as people, he added costumes, furnishing, and household items to his illustrations.

In the 1970s the children's book graphics became of impressionistic type. Artists often illustrated with watercolors; works of Juvenal Korovin are a good example. He was a remarkable book illustrator, who became very well-known for his graphics for The Mail and A Good Day by Samuel Marshak, For Children by Vladimir Mayakovsky; Uncle Styopa by Sergey Mikhalkov, drawings for Russian folk tales, such as Morozko, Sister Alyonushka and brother Ivanushka, Teryoshechka and etc.

Robert-Jan Henkes, a translator, spoke about illustrations for What is good and what is bad by Mayakovsky from the 1930s and read the Dutch translation of this well known poem for children.

The event ended with the presentation of a story-book by Boris Zhitkov, a Soviet writer. The book was translated into Dutch and adapted for young Dutch readers. Ari van der Ent, a translator and a publisher, told about Tom the Whyer (the original character of Zhitkov’s stories was a boy Alyosha nicknamed "The Whyer").

The meeting was attended by students of Slavic languages, teachers, writers, artists and journalists. The most common questions from the audience were the following: “How come there are so many children's books in Holland?” And “Why is Soviet children's literature in such high demand even now, when the USSR ceased its existence in 1991?” Collectors and researchers shared that Soviet books came to Holland in different ways. Collections compilation started long ago, and many books were bought from Russian émigrés of the first wave in France. During the Perestroika, people in Russia and the former Soviet republics willingly sold children's books for currency or even threw them away. The challenge was to find sellers and those who wanted to get rid of thin children's books.

“Soviet children's books by Chukovsky, Marshak, Mikhalkov and Zhitkov will always be popular in Russia and throughout the world, because they represent high-quality children's literature,” said Ellen Rutten to answer a question from the audience.

Collections of the Institute of Social History contain about 550 paper books for children dated back to the Soviet period. The most complete collection of Russian and Soviet children's books in the Netherlands, and perhaps in whole Europe, belongs to the Abbe Museum in Eindhoven, a leading museum of modern art. There are about thirteen thousand copies of children's books published in the period from pre-revolutionary time to today in the vault of this museum. All those books have already been digitized.