Science, emigration, and mission of Russian women

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Science, emigration, and mission of Russian womenScience, emigration, and mission of Russian women

Sergey Vinogradov

In February, the House of Russia Abroad launched Portraits of Women in the Russian Scientific Community Abroad in the 20th Century, a series of public lectures. In the lead-up to International Women's Day, we talked with Natalia Masolikova, the author of the series, about how Russian women emigrants made their way to scientific heights, and what united them despite all the differences in characters and destinies.

Natalia Masolikova. Photo credit: House of Russia Abroad

Without glass ceiling

– Russian women scientist abroad is a rather uncommon topic. It is a borderline between gender studies and studies of emigrantica. Why did you choose this topic?

– It would be a high-flown talk to say that this is the topic of my life. I have been studying this topic for the last 10 years. It came in a simple, yet interesting way. I have a degree in psychology, and gradually I came to research the history of Russian psychology. At the House of the Russia Abroad, I was offered to cover this very thread within the scope of studies of scientific emigration of the first wave. These are not only emigrant psychologists, I also look into medicine, pedagogy, and, sometimes, the social movement, because psychology in Russia did not mature as a science at the beginning of the last century, and people of very different professions took part in its early days.

– Your lecture series feature not only psychologists; there is also a veterinarian and a microbiologist…

– While working on the subject-matter, there come some stories that are just impossible to ignore. This is how a small pool of female emigrant stories related to science was formed.

– After the revolution, was a Russian woman scientist abroad rather an exception?

– No, not an exception, but also not a mass phenomenon. It was a completely natural process. There were women scientists before the revolution, there was also scientific emigration even before the regime change in 1917. But, as you know, back then, there was a problem with women acquiring higher education in the Russian Empire, and those who wanted and who could afford it financially, moved abroad, mostly to Switzerland, Germany, and France, for this very purpose. Of course, women scientists were inferior to men in terms of their count, but no other criteria.

Now it is a fashionable trend to claim that all roads for women were closed. Studying facts, archives, memoirs, I do not find any confirmation of this on a massive scale. When it comes to the career development of women, there is such a well-known term as the glass ceiling. So, none of the heroines who we will talk about within the framework of the lecture series this year actually had this glass ceiling. Moreover, those men who surrounded my heroines on their career paths most often turned out to be their guiding stars by providing not only financial support, but rather professional and friendly ones, as well as guidance, promotion, talent assessment, and so on.

– Russian literature describes a noblewoman who wholeheartedly wants to be useful but often does not find an opportunity for this since there are no educational institutions. How did the heroines of your lecture series manage to achieve high academic degrees and leadership positions?

– This is a kind of broad-ranging question. There are different women, different circumstances, and different stories. For some, the path to science was associated with family capabilities and traditions - they continued the scientific endeavors of their parents or had financial resources for education abroad. But there are other stories when the woman did not have any of the above when the heroine reached certain heights only through work, charisma, character, will, and coincidence, including, by the way, the revolution-related events.

Contrary to common stereotypes, the revolutionary period was not only about doors closed for professionals. As in any controversial time, there were also opportunities, including those for self-realization, that became available for women and had not existed before. And yet, certain circumstances resulted in the fact that our heroines moved abroad, and in most cases, they moved on their own. Interestingly, the philosophers' ships were, rather, a men's story. Basically, women have different psychology from men, and they approach survival differently.

Russian utopia in faraway lands

– Becoming a recognized scientist, especially in a foreign country, requires tremendous willpower and outstanding character in addition to talent. Did your heroines have those?

– It seems to me that their stories are not about pushy temper or power. What is more, sometimes you see their portraits reflect more fear and anxiety than firm confidence. Although there are different cases. For example, Nina Bouroff was a graduate of the Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens, the wife of a colonel, a mother of two children, a member of the White movement, also known as the Maikop Atamansha, a sentenced to death prisoner in solitary confinement, a prisoner of the Solovki special camp, who fled and illegally crossed the borders of several countries to reunite with her family, and later in emigration - an artist, art critic, public figure, writer, psychologist, and teacher.

But such stories are few. Again, most of those I am talking about did not thrust their way or break walls in our understanding. I have my own definition, perhaps controversial, and nevertheless: these women were guided by their Russianness (I really like this little-used word). Russianness can be seen as an initial womb (family, culture, language, traditions), as a direction, as a source of energy. Perhaps the main thing that unites my heroines who were so different is a kind of unintentional missionary work, an idea, the importance of the cause, humanism. After all, an emigrant has different survival strategies to choose from - to adapt in such a way to be just the same and clearly emphasize his nationality, or to assimilate in a new environment, taking the past as the foundation and adapting to the surrounding as much as possible.

Nina Bouroff. Photo credit: LitPrichal

My heroines remained Russian inside while becoming French, Brazilian, etc., and bringing benefit and knowledge to other countries. At the same time, even the scientific activity of Russian women acquired some specific features. There was always some kind of humanistic component. It was always about a kind of spiritual mission on top of laboratory works, and it is very interesting to study this topic.

– Does it mean that they were raised and highlighted by the era?

– It is an interesting remark that makes sense. Most likely, they would not have been mediocre persons if it was not for the cataclysms of the era. But history does not know the conditional tense. Dramatic historical events in their homeland did play a really important role in their lives. You know, this is similar to how a crisis is understood in psychology. On the one hand, everything is bad and everything is collapsing, but on the other hand, this is a stage to exfoliate the unwanted things and mobilize power, which triggers the abilities that you did not even suspect about a day before.

– You have already given a lecture about Helena Antipoff, an outstanding psychologist who developed the education system for children with special needs in Brazil. Are you more interested in her as a psychologist or as a Russian woman who was able to realize her potential on the other side of the world in difficult times?

– We discovered this name 10 years ago and almost immediately went to Brazil to research her archive. Ever since she has captured my mind. The story of Helena Antipoff is amazing; I don't know any other story like that. A woman who grew up in the family of a Russian general, after receiving a brilliant psychological European education, went back to her homeland, to the burning hell, in 1917, and ended up literally at the forefront of psychological and pedagogical work - for five years she worked with street children, orphans in children's distribution centers in Vyatka and St. Petersburg. Then she emigrated. First, she was in Europe again; from there she went to Brazil, about which Russian travelers of that time wrote that only the desperate could stay and live here. Look at her photo - a slender, modest, intelligent woman, she did not have any pushy temper, but there was the moral courage, that is beyond any doubt.

Helena Antipoff with children. Photo credit: museus.cultura.gov.br

In Brazil, she realized Russian utopian dreams - an equal approach to all children, educational salvation for those who were different or in need. You asked what I find interesting about her. It is everything with no exceptions. I am interested in her as in a Russian mother, whose son hardly spoke Russian since the age of 10, in the wife of the exiled writer Viktor Iretsky, in an emigrant who built her own city of the Sun in a distant foreign land, and, of course, in a professional psychologist. I think we have underestimated what she did in the profession - we still need to translate her 5-volume archive of works from Portuguese, and this is our task for the future. There are public initiatives, the author's methods, lectures, and her own system for diagnosing and teaching children with special needs.

– Your next lecture will be dedicated to Olga Uvarov, the outstanding British veterinarian with Russian roots. Why is her fate interesting?

– Olga Uvarov (1910 – 2001) ended up in Great Britain in her childhood by accident, as a "parcel" delivered by the Red Cross. I can't even say otherwise. Boris Uvarov, Olga Uvarov's uncle who was another famous Russian Briton and entomologist, bought his niece out from Soviet Russia, and she was transported with the help of the Red Cross.

Olga Uvarov. Photo credit: Karl-August / Kak prosto!

Speaking of Uvarov’s story, it was actually about breaking the glass ceilings. In the UK back then, women hardly worked in veterinary medicine, and they were not promoted above an assistant or nurse. And Uvarov managed to become a private veterinary surgeon, and later - the first woman president of the Royal Veterinary College. Her portrait is in the National Gallery of Great Britain, and the college awards the best students with the Dame Olga Uvarov scholarship. Even a flower, one of the orchid species, is named after her. At the same time, we must not forget that Great Britain was a very difficult country for the emigration of Russians at that time, only a few stayed there, and it was more than difficult to walk their way up the career ladder.

– Did Russian women assimilate, merge with the environment abroad? Or did they keep their Russian identity? What stories do you see more often?

– Perhaps it will sound somewhat pompously, but I really see this - our heroines accepted with respect (accepting the rules) and interest (adopting to and transforming) the environment that let them in; at the same time, they did not emphasize their Russianness but fed on it. Their nationality was manifested not in their activities within the Russian diaspora, but in their professional actions, in the ultimate goal for the sake of which these women worked. I have said many words of praise, while their lives were not showered with honey.

Let us look at the story of Elizaveta Volman, who went to France and worked for Pasteur Institute. She had her own laboratory, a good salary, successful husband. In 1942, she refused to leave Paris to save her life. As a Jew, she was betrayed and arrested literally at the workplace. She died in Auschwitz. Why didn't she and her husband leave the institute when the staff had such an opportunity? Reading the memoirs about personalities of these French scientists, we learn that the spouses simply could not leave their brainchild, the alma mater, to stop the production of anti-gangrenous serum, which had commenced, as well as other important researches related to, by the way, viruses and bacteriophages. They could not betray their missions. From my point of view, this is what Russianness is about.

Elizaveta Volman. Photo credit: gallica.bnf.fr

New publications

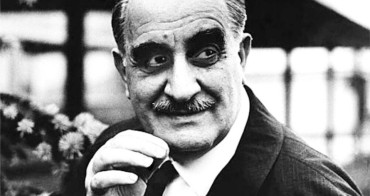

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

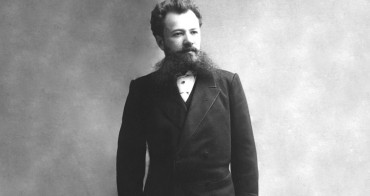

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

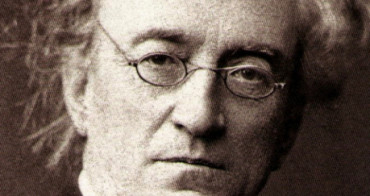

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...