Proud of Our People! Mikhail Kalatozov, gravity-defying cinematographer

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Proud of Our People! Mikhail Kalatozov, gravity-defying cinematographerProud of Our People! Mikhail Kalatozov, gravity-defying cinematographer

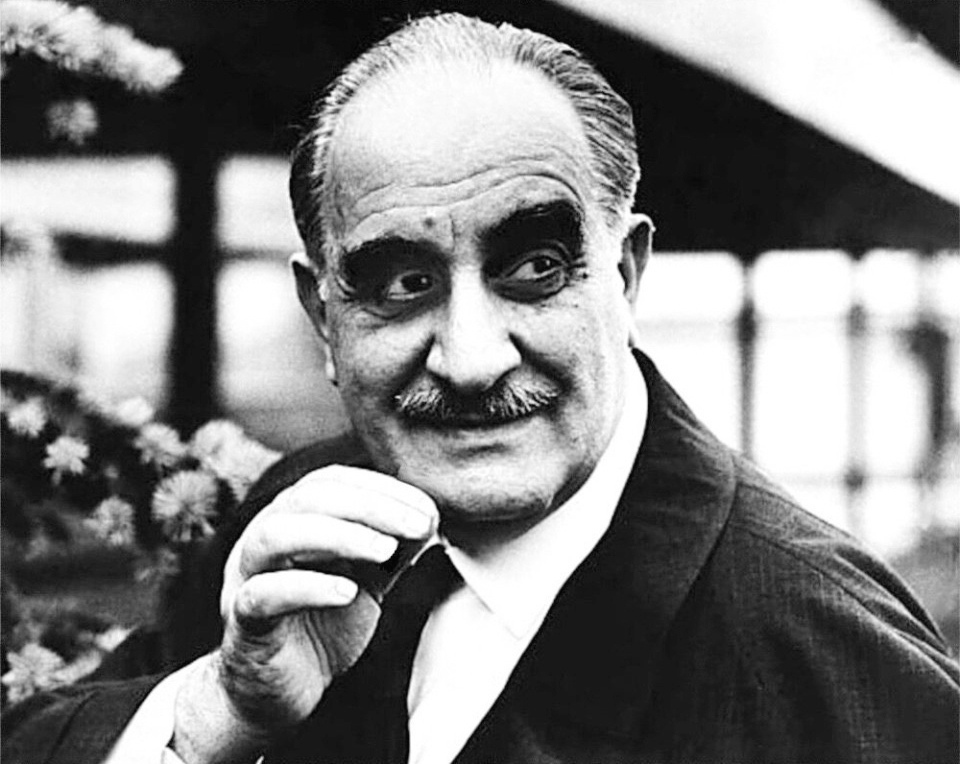

Mikhail Kalatozov

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Prince, Rabfak's Student, Romantic

One of the most talented Soviet film directors of the 20th century was born in Tiflis on December 15(28), 1903, 120 years ago. Mikhail Kalatozov came from a noble Georgian family. Many Georgian intellectuals visited the house of the Kalatozishvilis (that was his real family name). His father was an agricultural engineer, and the boy studied at a technical school. However, the Revolution of 1917 changed everything. At the age of 14, Mikhail started working. Then, he wanted to complete his education, so he joined the Rabfak (an educational organization that prepared Soviet workers to enter institutions of higher education).

Young Kalatozov tried a lot of occupations. Yet, they all were associated with cinematography. First, he was a chauffeur at the Tiflis Film Studio. Then he was a tape gluer, assistant, assistant cameraman, second director, editor, as well as an actor and scriptwriter. That is, he experienced everything available in the cinematography and gained invaluable knowledge. Most importantly, he learned to find new, unconventional ways in art.

In the 1920s, Mr. Kalatozov wrote scripts and acted in films produced in Tiflis (contemporary Tbilisi.) He made his debut as a director with Their Kingdom in 1928. He co-directed it with Nino Gogoberidze, one of the first female film directors in the USSR. Two years later, there was the first resounding work in the young cinematographer's career. In 1930, Mr. Kalatozov released Salt for Svanetia, a feature documentary about the inhabitants of Svanetia, which was warmly received by critics.

Mikhail Kalatozov's signature style could be clearly recognized in that work, including the great attention to domestic details, and lifestyle of workers. Nevertheless, everything was shown in an extremely lyrical way, for instance, the expression of a strained body performing hard work against the backdrop of a vast sky and the immense nature of the Caucasus Mountains.

The romanticization of nature, high mountains, vast expanses, and the heroism of a small man against their background, tense faces in close-ups, and the dynamic scenes of frenzied movement became hallmarks of Mr. Kalatozov's work. The following films by the director became milestones in this sense: Courage (1939) about the sky conquerors, and Valery Chkalov (1941), a story of the famous Soviet pilot.

Much later Mikhail Kalatozov shot Letter Never Sent (1959) dedicated to young geologists conquering the huge Siberian taiga. Despite many close-ups, there were hardly any static scenes in that film. Even when the two protagonists are talking to each other in the frame, you can see their hair fluttering in the harsh Siberian wind. Such features add special dynamics and drama to the entire movie.

"The image of the rugged northern nature is meticulously compiled from episodes and frames. This image is impressive and overwhelming. It is consistent and complete, although there were several shooting locations, including the basin of the Yenisei River, the construction site of the Krasnoyarsk hydroelectric power plant, in the taiga gorges of the Sayan mountain range, and the Usinsky Tract..." wrote about this film G. Kremlev, Mr. Kalatozov's biographer.

The taiga expedition for filming Letter Never Sent was an extraordinary experience. "We're rooting out trees and moving rocks to set new filming locations. It feels like we've dug up the whole taiga. We are taking dry wood to a high hillock... We start setting out a hundred-meter-long fire panorama at dawn, at five o'clock in the morning…

We persuaded Mr. Urusevsky, a cameraman, to wrap him up in asbestos so he could shoot the flames from within the fire. His vatnik caught fire despite the asbestos. It was really hard to beat it down. He was angry as it disturbed him from finishing filming", one of the crew members wrote in his diary. The above describes the directing style of Mikhail Kalatozov.

By the way, Tatiana Samoilova, a leading actress, suffered burns to her legs and hands during the filming of this scene. Well, the team was young, enthusiastic, and had a good sense of humor, which was a definite advantage in those harsh conditions. For instance, there were humorous inscriptions on actors' trailers in the taiga: "Fire-resistant Smoktunovsky", and "Water-resistant Livanov".

During the war, Mr. Kalatozov and Sergei Gerasimov produced The Invincible (1942), a dramatic war film about the Leningrad siege. It was shot right in Leningrad during the siege, as both directors worked at Lenfilm at that time.

The Cranes Are Flying (1957) Palme d'Or at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival

Slap in the Hollywood Face

In 1943-45, Mr. Kalatozov traveled to the allied USA to establish business ties with Hollywood studios and arrange for the reciprocal distribution of films. Moving forward a little, we should mention that no agreement was reached. The American "partners" were eager to enter the vast Soviet market. However, they refused to distribute Soviet films under the pretext that their subject matter was too specific and would be incomprehensible to the American audience.

Mr. Kalatozov encountered many prominent and influential representatives of the moviemaking industry, such as Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, William Hayes, Louis Meyer, and others, and gained a very good understanding of how the American filmmaking business was organized. He wrote The Face of Hollywood (1949) with very interesting memoirs about this.

Having observed how film production was managed in the United States, Mr. Kalatozov found it useful to adopt American methods. He recognized the enormous impact that cinema had on the American public. However, there were many aspects of Hollywood that he could not accept.

"I watched four hundred and seventy-three movies while in Hollywood. Only six of them were actually noteworthy," Mr. Kalatozov wrote in his book.

The Soviet director criticized the poor cultural level of Hollywood producers and actors, as well as the prevalence of the mainstream and cliches. "There are few Hollywood filmmakers determined to have the movie free of the author who admires his trivial wit, actors who are in love with themselves and admire their monotony, the cameraman who admires the standard light, and most importantly, the producer who admires his vulgar preferences," he wrote.

In some cases, the situation with Broadway theaters was better.

"The entire Soviet society embraces art and literature with exceptional attention and care. America has a completely opposite attitude toward art, a merely speculative one. I realized this sad truth for the first time when I watched theater performances in New York.

<…>

Back then, Mae West's performance as Catherine the Great was a sensation in New York.

Mae West was the most popular "vamp" in the early cinema. She created the image of an adventuress and "queen of love" that was imitated by young actors in American movies for many years.

Theater entrepreneurs decided to revive the relics of silent cinema looking for profit. They took a chance on old Mae. They sent her to a beauty institution, massaged her, applied some makeup, and she was back on the stage of Forty-third Street performing her role again. All scenes of the vaudeville take place in one set, which is a huge bed of the empress. Mae West (Catherine the Great) gradually throws off one piece of her attire after another and finally finds herself completely naked. While solving "state" affairs, Catherine the Great is having fun in her bed with all the Russian nobles and foreign ambassadors who come to see her. The absolutely indecent text somehow binds this unsophisticated plot altogether.

<…> There was a notice "Full house for the whole year" above the box office of the theater where the "historical" vaudeville was performed. Tickets could be purchased from the policeman on duty only, of course, at extra cost" (M. Kalatozov, The Face of Hollywood, 1949).

Mr. Kalatozov did recognize Hollywood's potency, its high efficiency in producing a huge number of films, and its influence on minds. He believed that the postwar US film expansion had caused the national filmmaking industries in the leading cultural countries of that time (France, Italy, England) to be suppressed...

It was Mr. Kalatozov who headed the Soviet delegation to the first Cannes Film Festival in 1946. According to the director, it felt as if the Soviet and American cinematographs clashed to gain influence in post-war Europe. It was a direct clash of ideologies and artistic principles.

The Soviet Union won that battle at Cannes. It received eight prizes, including the Peace Prize. The United States got three prizes. When the winners were awarded, the US delegation walked out of the room. "The world had never seen Hollywood in such creative squalor as it did at the Cannes Film Festival," Mr. Kalatozov wrote. He suggested to use the cinematograph as a tool for the propaganda of Soviet ideas abroad.

Triumph at Cannes

Well, The Cranes Are Flying (1957) was the first Soviet film to win the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It became the director's personal triumph. This film has been considered a classic of both Soviet and world cinematography.

Sergey Urusevsky, an outstanding cinematographer, co-produced the film. It stood out for its innovative cinematic language, which resulted in a heartfelt, dramatic, yet lyrical story about people's difficult fates during the Great Patriotic War. No one had ever spoken about the war in this language before.

The film made a strong impression in Europe. It inspired Claude Lelouch to start making movies. Having watched it, Pablo Picasso said that he had "not seen anything like this for ages".

In 1964, Mikhail Kalatozov and Sergey Urusevsky went to Latin America. It was 40 years after Sergei Eisenstein and Eduard Tisse's trip to Mexico that Soviet filmmakers of a new generation had an idea to make a film about a nation fighting for freedom. The plot was truly epic and featured the events of the Cuban Revolution. The script was written by the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

I Am Cuba was Mikhail Kalatozov's last great work, a poetic reflection on the revolution's events. Yet, his contemporaries failed to understand and appreciate it, be it in the USSR or in Cuba. The film was nearly forgotten. In the mid-1990s, it was restored and returned to viewers through the efforts of Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese who recognized Mikhail Kalatozov's creative legacy and its significance. Thus, the new Hollywood generation has admitted their respect for the Soviet school of cinematography and its outstanding representative.

New publications

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...