Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language. Marco Maggi: ”Russian to the Bone"

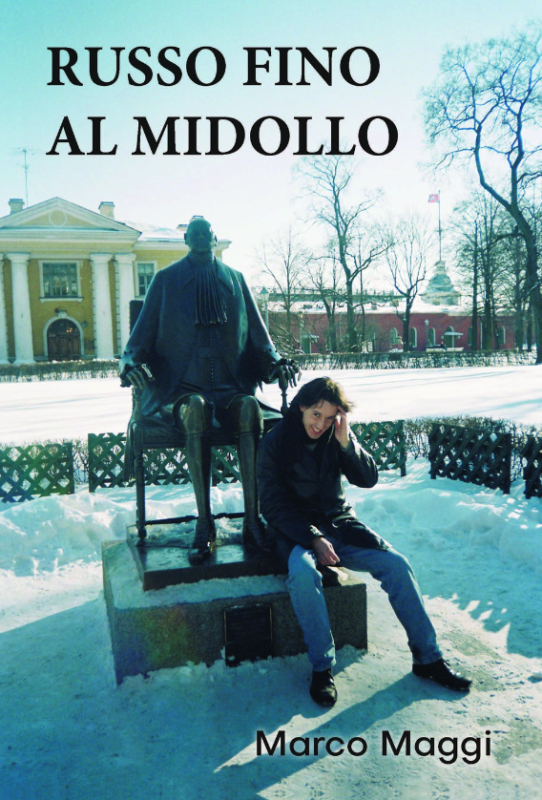

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Marco Maggi: ”Russian to the Bone"Marco Maggi: ”Russian to the Bone"

Anna Genova

Photo: Marco Maggi

Italian entrepreneur Marco Maggi's book, "Russian to the Bone," is now accessible for purchase in Italy and is scheduled for release in Russia in the upcoming months. In the book, Marco recounts his personal odyssey, narrating each stage of his life as a foreigner in Russia—starting from the initial fascination to the process of cultural assimilation, venturing into business, fostering authentic friendships, and ultimately, reaching a deep sense of identifying as a Russian at his very core.

- Marco, you have not only lived in Russia for 20 years, not only built a career there, but also written a book about this amazing period. What prompted you to do this?

- For a long time, I had intended to share my experiences in Russia but never found the opportunity to do so. It took an unexpected turn of events—my illness and the "forced vacation" in Rome for treatment—to grant me the ample time I needed. Suddenly finding myself 3,000 km away from my family, work commitments, and the familiar faces of St. Petersburg, I underwent six hospitalizations at Gemelli Hospital in Rome, each lasting between 30 and 45 days. It was during these times of isolation that I penned most of the book.

In the randomness of the situation, I believe I stumbled upon the perfect historical moment to recount my Russian adventure. In an era when Russia was often portrayed negatively and demonized in Western countries, I took a different approach, portraying it as a fantastic country full of opportunities waiting to be discovered.

- Your wife has helped you to deal with Russian realities. You wrote about her and your first years a lot. In most cases, Russian wives move in with their Italian husbands. Why did you make such an atypical choice and moved yourself?

- Before coming to Russia I lived in many other places in world. I even lived a few months in the United States, but I didn't like it at all. In the early 2000s I sensed that there were not many opportunities for young people in Italy. Russia struck me immediately, I saw in the still unstable and strongly developing situation of the early 2000s the possibility of doing business in many areas. Low competition, simplicity in opening a company without the need for initial funds, a kind of simpler and more affordable world. I also liked the people, clearer and more direct, less hypocritical and more real. My wife then, despite the clichés, did not want to come to Italy. She was doing very well in St. Petersburg, she had a good job and the house that her older sister gave her free to use.

- You describe how difficult it was to switch to Russian language with your wife, as she knew English perfectly well. What advice would you give to Italians and, in general, to any foreigners who really want to learn Russian well?

- I certainly did not learn Russian with my wife, but with my first business partner, Dmitry. He spoke exclusively Russian, so I had no choice! One of the tips I give in the book is this: don't socialize only with Italian or English speakers, instead surround yourself with people who speak only Russian. It’s the only way will you be "forced" to understand and speak it. School courses help to know the alphabet, words and the basics of grammar, but without direct experience you will get nowhere. And don't worry if you make mistakes, I still do after twenty years. If you stand there just coming up with the right sentence wording with the right verb and the right case, by the time you put the sentence together your friends are already talking about something else! The important thing is to understand and be understood, without being afraid of making mistakes. You will expand your vocabulary and refine your grammar step by step.

Photo: "Russian to the Bone" book by Marco Maggi

- Here's a quote from your book, “I wondered how they could survive in the winter in that cold weather.” I would ask you the same thing!

- Well, in that sentence I was referring to the homeless. In the early 2000s there were a lot of them in St. Petersburg, especially near metro stops and churches. Then the situation has clearly improved. Now on the contrary many more homeless people can be found on the streets of Rome, Milan, Paris, New York... in the very center and near the most famous streets and monuments. I now how they survive the winter in Rome! The heaters are so weak and the apartments are so poorly equipped for winter (walls that are not very thick, windows often still made of wood and without double glazing, heated floors that with the prohibitive prices of electricity no one has, etc.) that even if it's 10 to 15 degrees outside, you freeze in the house and stay with your sweater and blanket watching TV. Here at my place in Rome is 15 degrees inside the house. Accustomed to the warmth of St. Petersburg, where it's at least 25 degrees inside the and you stay in your underwear even though it's freezing outside, I can now say that it's colder in Rome in winter!

- You write that you were often taken to hospital by ambulance because of food poisoning in the beginning of 2000s. Is Russian food so hard to digest for an Italian?

- Well, let's say that an Italian is strongly accustomed to his food and rarely abandons it, no matter what country he is in. Russian "makaroni" are a side dish that is used now and then, for Italians they are the unfailing highlight of every self-respecting lunch and dinner. I was an Italian who grew up in the fantastic 1980s and had more delicate stomach than a Russian who went through the years of perestroika and Yeltsin democracy. In the early 2000s the product quality and hygiene standards were quite low, so the risk of food poisoning, especially for an Italian like me, was high. Afterwards, along with my “Russification" and the certain quality standard raise, the problem was solved.

- What aspects of life in Russia posed challenges for you to adapt to, and which ones were relatively easy to embrace?

- In my book, I recount the period when I relied on the marshutka to commute to the Smolny Institute for my Russian class. There was always the uncertainty that the driver might not hear or understand me, or that I could misinterpret the correct place to disembark. Such a mode of transportation, with no predetermined stops and reliant on vocal calls, was unfamiliar to me, as Italy lacked such systems. This posed challenges, especially during my initial attempts to purchase goods or subway tokens, where my foreign accent or a slight linguistic misstep resulted in perplexed stares. The locals appeared rigid and courteous, displaying impatience and frustration when faced with my linguistic struggles. However, as I gradually pieced together coherent sentences and made myself understood, there was a noticeable shift in their demeanor, suddenly, they became more friendly and helpful.

Initially, I found it disconcerting to sleep without the blanket being securely fastened to the bed. In Italy, the practice involved tucking the sheet under the mattress and placing a blanket on top, creating a sense of enclosure and protection. Conversely, in Russia, the use of a loosely draped comforter without any fastenings was the norm. Over time, I adapted to this and now prefer sleeping in this manner. On the other hand, one aspect I quickly embraced was the lack of obligatory pleasantries and smiles.

In Italy, even if you displeased by a neighbor, exchanging greetings like "Buongiorno, come stai?" (Good morning, how are you?) with a smile is almost obligatory, especially in an elevator. In contrast, in Russia, there was the freedom to comfortably disregard each other, a preference of mine as I've never been a fan of putting on a facade in relationships.

- You opened your travel agency in 2004. What were the challenges you faced?

- I faced no challenges because my Russian partner was already experienced and handled everything. Back then, there were no licensing requirements to establish a tourist agency or tour operator, and no significant capital was necessary—just 5,000 rubles each for a table and a computer, and you were good to go. Specialized agencies took care of the documentation for a reasonable fee, creating a system that felt like a parallel universe compared to the complexities of opening a business in Italy, where licenses and substantial initial capital are prerequisites. Initially, our focus was on daily rental apartments for Russian clients, with our primary competitors being individuals at the station advertising "sdam kvartiru." Gradually, we expanded, moving up from competing with small tourist agencies to contending with major tour operators.

- You write a lot about the friends and associations that support you. One of them is Italians in Crimea.

- Sure. In recent years I have developed many mutually beneficial contacts with both Italian and Russian associations. We visited the community of Italians in Crimea in Kerch in 2016, by the invitation of Igor Ferri who was part of the steering committee at the time. Putin and Berlusconi had been there on a visit just before us. During that trip, any lingering doubts about the legitimacy of the 2014 referendum and the positive outcome of Crimea's reunification with Russia were completely dispelled. The people I encountered on the streets and the taxi drivers with whom I conversed were unmistakably Russian, and their overwhelming sentiment was one of joy at being back in the motherland. None of them mentioned coercion or irregularities in the voting process; rather, everyone I spoke to emphasized that they had willingly and consciously participated in the referendum. By 2016, we could see clear improvements to roads and infrastructure, after the two-decade-long stagnation during Ukraine's control… They works on the Crimean bridge just started, it was amazing then how quickly and efficiently the work was completed.

- You express criticism towards the Italian press. From your perspective, which country experiences more censorship, Russia or Italy?

- In Italy, the press is predominantly influenced by commercial entities with connections to the United States. Contrastingly, in Russia, it is primarily under state control, aligning with the interests of the nation. Italy is often characterized as behaving like a U.S. colony, lacking sovereignty and an independent foreign policy, merely adhering to directives from abroad. The newspapers reflect a singular perspective, creating a homogenous narrative; reading one is akin to reading them all. While people may believe they enjoy freedom, diverging from the established narrative can lead to social ostracization or professional repercussions, especially in journalism or media roles. Although individuals aren't physically removed, they risk disappearing from television or newspapers if their views deviate from the mainstream. Exceptions exist for prominent journalists with sufficient influence to occasionally express unconventional opinions. Notably, social media in Italy is subject to a sort of "Ministry of Truth," where fact-checkers determine what is deemed acceptable for publication, imposing bans and censorship to limit counter-information. Such controls appear less evident on Russian social media platforms.

- Italy has always had a strong socialist party. And still in some regions you can find Lenin's street or even a monument to him. Now the 1980-90s bands CCCP Fedeli alla linea and the reggae band 99 Posse have become very popular again. A couple months ago, 99 Posse unfurled flags of the LPR and DNR while performing at the People's Recovery festival in Naples. What is this all about?

- There are frequent examples of diametric divisions in society in Italy. Think of the Second World War. There is always a part of the population strongly committed to one side, and another side strongly committed to the other. And there are those in the middle, those who go where the wind blows. They just adapt to what is convenient at the moment. Even now, regardless of pro-socialist or pro-capitalist views, people can be either pro-Atlanticist or the complete opposite, perhaps with sympathies for Russia or a multipolar world. The movement is cross-cutting and includes people on both the right and the left. Speaking of the left, there is a big confusion in Italy, because what was once the PCI (Italian Communist Party) and very closely linked to the Soviet Union, has gradually turned into the PD (Democratic Party) inspired by the US Democratic Party and its ideals. Now they don't anymore defend workers, but minorities like LGBT+ and political correctness. There has been a short circuit! The party that represented the Sovereigntist right wing, once in power, has turned out to be one of America's worst lackeys. In opposition they say one thing, and in government they say another. Ordinary people, on the other hand, have little idea of the actions of their politicians; they are sick of voting because nothing changes in the end. In Italy, however, there are many more Russophiles than it seems, they just prefer not to show it.

- Marco, the situation still remains difficult, Russians continue to experience sanctions. In your book you write, "The sanctions have also brought benefits: they have given a significant boost to domestic production and launched processes of nationalization of foreign factories and companies.”How has this situation affected you personally?

- I am one of those who has definitely been most affected by the sanctions. Being in the tourism business and having 98 percent of my clients coming from Italy, with the blockade of direct flights and banking sanctions I found myself in a great difficulty. Nevertheless, having now become Russian by passport and in soul, I did not give up and found ways not to give up and continue working, as did many Russians. On the other hand, numerous sectors, shielded from foreign competition, have experienced significant advantages due to sanctions. The restrictive measures have acted as a catalyst, fostering the emergence of new businesses and encouraging the establishment of domestic production lines.

I, unfortunately, was also a victim of the sanctions from the point of view of my health problems. I would have liked to continue my treatment in St. Petersburg after the first round of treatment in Rome, but my hematologist pointed out to me that because of the sanctions there was a severe shortage of the oncology medicine I needed, all of which were Western-made, and therefore they were unable to provide me with the treatment I needed at the time I needed it. Having the opportunity, I returned to Rome for treatment.

- Marco, our editorial team wishes you a speedy recovery, and Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

- Thank you for your wishes! I only hope for the best. I hope the New Year brings us good luck!

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

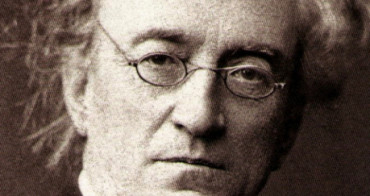

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...