Plus Twenty

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Plus TwentyPlus Twenty

The fact that the 1,020th anniversary of the baptism of Russia would differ fundamentally from the 1,000th could have been predicted long before the date itself. All the realities that existed in 1988 – state, political and ideological – have since disappeared, which, of course, requires us to rethink the colossal events that took place more than a thousand years ago. This is natural. Colossal events do not lend themselves to a single interpretation that can stand once and for all. It is always possible to draw attention to other aspects of any given event, or to consequences. Something that could be taken for granted 20 years ago now requires an explanation, and vice versa. In many ways, therefore, history will never be treated as a precise science. Any society will continually reevaluate its attitude to its own past, and it will do so simply because new experience has been accumulated.

The differences between the current anniversary and the one celebrated two decades ago were so dramatic, however, that they require further reflection. First of all, the only center of celebration this year turned out to be Kiev, which stands in stark contrast to the 1988 celebrations that occurred in all the historic centers of Orthodoxy in the Soviet Union. These included, of course, Moscow (it was at this time that the Danilov Monastery was handed over to the Moscow Patriarchate). The 1,000th anniversary and 1,020th anniversary – naturally different in terms of their “roundness” – probably should not have overlapped in terms of their scale and geography. However, the fact that the 1988 celebrations were held across the country had a major impact on the perception of the event and they gave us reason to talk about the contribution of the church to the historical and cultural heritage of our country and even recall the Orthodox tradition. After the 1,000th anniversary of the baptism of Russia, the Russian Orthodox Church began to steadily strengthen its position in society and in relation to the state. Soviet citizens were no longer shy about entering functioning Orthodox churches.

The location of today’s celebrations in Kiev automatically puts the accent elsewhere. The “baptism of Rus” has become primarily the “baptism of Kiev.” According to the chronicle, in 988, it was Kiev on the Dnieper that was baptized. But since Kievan Rus has long since ceased to exist, the concentration of all commemorative ceremonies in Kiev signals the importance not so much of the city’s role as the “mother of Russian cities,” but rather of the capital of modern Ukraine. If the celebrations were truly connected to the anniversary of Russia’s baptism, then apart from Kiev, festivities would also take place in Novgorod, Vladimir and Polotsk. The picture would look quite a bit different.

This situation can be viewed in another way, however. After all, 1,020 years is indeed a rather strange number to remember, which gives us a good reason to discuss why Kiev felt the need to celebrate it in the first place. Nobody seems to be hiding anything, though, and the Ukrainian authorities have demonstrated quite clearly that they expect the support of the Ecumenical Patriarch in establishing Ukrainian autocephaly and the subsequent merger of all existing Orthodox churches in Ukraine (the Ukrainian Orthodox Church under the Moscow Patriarchate, the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church and the Ukrainian Autonomous Orthodox Church – the latter two are not currently recognized by the Patriarch of Constantinople). Tying this merger to the anniversary of the baptism, while not to the most obvious anniversary, seemed like a good idea to somebody.

Bartholomew, as far as we can tell, has avoided showing direct support for the Ukrainian authorities, although one should hardly consider the matter closed once and for all. The very positioning of this issue itself is what is truly interesting here. The desire to obtain autocephaly does really exist in the Orthodox world, although often it is one that has been closely related to the “national revival” movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, this was how the Bulgarians achieved the recognition of their own national church. Against the wishes of Greek bishops and priests, the Bulgarians established their own exarch after appealing to the Ottoman authorities. This led to a Greek-Bulgarian schism in the 1870s (Constantinople did not recognize the Bulgarian church until the 1940s).

It is worth mentioning that one of the most attentive observers of the events in Bulgaria was a Russian diplomat named Konstantin Leontiev, who later became a well-known conservative essayist. In his articles “Again on the Greek-Bulgarian Conflict” and “Letters on the Eastern Affairs,” Leontiev shows extreme skepticism with respect to the Bulgarians’ desire for autocephaly, saying that the desire is not so much one of priests as the numerous nationalist intellectuals who are no longer believers but rather those wishing to adopt a “new Slavic, liberal religion.” Leontiev’s analysis is quite interesting in that it can be applied to similar cases, such as the establishment of Georgian autocephaly in 1917.

The difference between then and now is that in those years, the issue was one of creating nation states (or the desire to create them) according to the meaning of the word “state” as it then existed. In other words, a state was something with firm borders, strong customs barriers, a policy with respect to education and the maintenance of an army to either expand its borders or defend against neighbors (both were completely real possibilities). Moreover, as a rule, these were states in which the lives of many people were built around church parishes. In general, at that time, a national church and the inclusion of church issues in the nationalist projects were fully justified.

What is going on now in Ukraine gives us reason to think that the apologists of Ukrainian autocephaly are well versed in the essays of a century ago and that ideological development of their nationalism stopped at that point. How exactly the recognition of Ukrainian autocephaly by the Patriarch of Constantinople will be applied, not to mention the advantages it would have in a globalizing and increasingly secular world, is difficult to understand. How will this recognition in any way solve the issues that are truly facing society and the state (as opposed to those that are merely imagined)?

In this sense, the DDT concert on Kreschatik, which included Orthodox priests and Metropolitan Kirill, who pronounced: “Russia, Ukraine, Belarus – these are holy Rus,” took on the appearance of something suited to a much more modern agenda. The odd participation of Russian Orthodox hierarchs can be criticized in any number of ways. For example, one could talk about the excessive secularization of priests. One could also talk about how Metropolitan Kirill was using a revised quotation from Lavrenty Chernigovsky, who is known mainly for his apocalyptic prophecies and his claim that the name “Ukraine” was thought up by Jews in order to get rid of the hated word “Rus.” The concert that brought together an audience of 100,000, unlike the bookish dreams of Ukrainian statesmen, is nevertheless an appeal to real, living people.

New publications

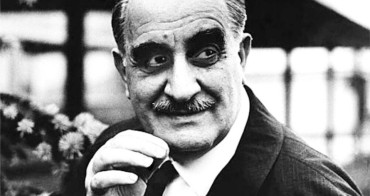

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

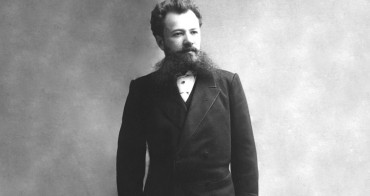

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

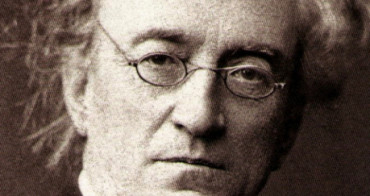

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...