Twenty Years of Lamentation

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Twenty Years of LamentationTwenty Years of Lamentation

Several years back the American research Nancy Ries gave me a copy of her book Russian Talk. She told me it was the result of several months spent in Russia at the time of Perestroika. She studied informal conversations of our compatriots, recording talks in kitchens and trying to make sense of them.

The most common genres of Russia conversation, according to Ries, were litanies and laments. And the ones to blame for all the problems were either the Soviet authorities, or in general “our country”, “the state”, “we” or some sort of irrational curse the hangs over Russia and its culture (which did not prevent her speakers from being proud of both). Attempts by the American woman to shift the conversation toward more practical topics – if something isn’t right here, then why is that the case and what can be done to correct the situation – were to no avail.

The book seemed quite engaging, but I didn’t have the time to read it. After flipping through it, I put it on my bookshelf where I keep my selection of foreign research on Russian life. But on the eve of this most recent Russia Day, I was invited to sit in on a radio show and speak with listeners about the state of affairs in the country. More precisely, about how people perceive the results of the past two decades and how they see the future.

The telephone was literally ringing off the hook. And to the clear dismay of the show’s host, out of the dozen plus callers that made it on the air, not a single one said anything good about modern life in Russia or the recent past. Twenty years ago these people complained about the lines and the communists, and today they complain about oligarchs and inequality. The complaints’ heores have changes, but the ton remains the same.

In a strange coincidence, on that very same day I happened across a Russian edition of Nancy Ries’ book and began reading it, recognizing these familiar and persistent themes. It should be noted that the specific content and even the ideological charge of Russian complaints has changed quite substantially over the last 20 years. But one thing has not changed – the desire to see all our problems as an irrational and immeasurable calamity accompanied by a complete refusal to view things analytically.

Of course, this does not mean that everything is fine and people’s desire to suffer prevents them from seeing these successes. No, there are very real reasons and grounds for these litanies and laments. The problem is not rooted in positive or negative thinking but rather in fact that this genre of thinking excludes understanding of the process. In other words, even if there are really reasons for it, the complaint remains empty.

Nancy Reis noted that the complaints of Russian intellectuals created in a sense of some sort of mystical-fairytale reality. In the remarks of her interlocutors, their home country is seen as an inexplicably cursed place, and the authorities belong to some dark force and follow the sole aim of doing their subjects as much harm as possible.

It is easy to see that these litanies and laments are nothing more than the flip side of bureaucratic boasting and official propaganda, in which every event is an achievement and every achievement is to the credit of officials. Both narratives – the official and the intelligentsia-oppositional – are identically irrational, but it is difficult to expect more from bureaucrats who after all are just defending their right to power. But from the intellectuals it seems to would be reasonable to expect critical analysis.

Even concepts that have very specific definitions, for example, capitalism, are turned into abstract symbols that mask (depending on ideology) either some sort of global evil or a certain ideal world order that the “civilized world” has long enjoyed but for some reason is not achievable here at home. If in Russia capitalism did not turn out as ideally imagine, then a liberal intelligent makes the one and only possible conclusion that either we do not have capitalism or someone has corrupted it. Someone or something gets in the way. The idea that the problem could rest with the speaker, with his own idealized perception of capitalism for some reason never occurs to him. Not to mention the fact that capitalism itself might have some drawbacks and contradictions… Such sacrilegious suggestions are out of bounds.

Nancy Ries compared the structure of the stories she heard with the structure of fairytales described by Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp. For example, comparing the contemporary story about grandmother going out for sugar with the story of the adventures of Ilya Muromets or Ivan Tsarevich and Vasilisa the Wonderful. Moreover, in Propp’s Morphology of a Folk Tale, there is a recurrent persona who regardless of name is called the villain. This is the person who is to blame. One person, a group or collective image of evil – if not a dragon than bureaucrats or communists. Recently, alongside side “oligarchs”, “Jews”, “Chekists” we now have “cops” which have taken on the role of the dragons of old.

Many of the villains exist outside the tales as well. It’s quite reasonable that in search of an answer to the question “who is guilty?” we find ourselves at the gates of oligarchs’ mansions or the doors of bureaucrats’ offices. After all, someone is making these ludicrous, harmful and absurd decisions that send the heads spinning of thousands if not millions of people?

But therein lies the problem. These decisions are not being made out of some mystical striving for evil but rather as a result of a certain system of logic. The question is not about who made this or that decision, but rather about why these decisions were made. Why were the circumstances such that it was not possible to make a different decision? And subsequently, it would be good to know how to change these circumstances.

But this pragmatic question still remains outside the classic Russian genre of lamenting. If something changes, then it changes somehow on its own accord independent of us, and as a rule for the worse. Are we really incapable of affecting the situation? Nancy Reis was bewildered as to why such topics were automatically dismissed as “American”. And as she concluded her research, she herself began to see discussion of practical constructive actions as an American genre. Alas, 20 years later the situation has changed very little. The Russian intelligent can quite eloquently lament about domestic life but he still hasn’t learned either to explain it or to change it.

There is a joke I remember from Soviet times. An American, Pole and Russian are asked why there are lines to buy meat in the USSR. The American, instead of answering, asks: “What are lines?” The Pole asks: “What is meat?” And the Russian asks: “What do you mean by ‘why’?”

Unfortunately, a quarter of a century later, this joke still hasn’t lost its meaning.

New publications

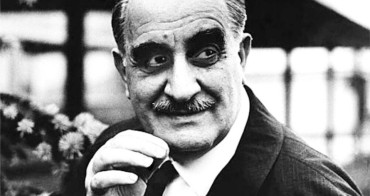

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

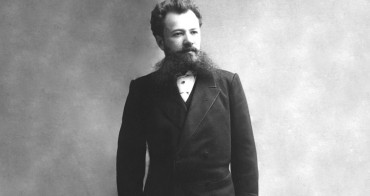

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

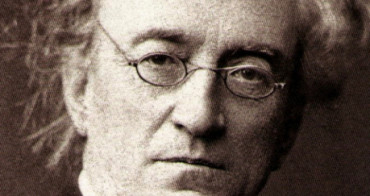

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...