Soviet Nostalgia

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Soviet NostalgiaSoviet Nostalgia

We began to hear reports that the Soviet era was coming back into fashion in the early 2000s. And it’s no surprise. Following the painful revelations of the previous decade and the lack of any sense of measure among the castigators of the Soviet era, who themselves did not put their best face forward, nothing less should be expected.

The swing of the cultural pendulum is rather logical. The dismal monotony and vapidity of the Brezhnev era made people dream of something new, something different. It forced them to imagine a different life. Everything that stood in opposition to thing Soviet became interesting and exciting, be it the pre-Revolutionary era or life in the West, of which people really no more than the romantic eras of the past. But after the period of stagnation became a thing of the past, and the lives of millions were changed and not for the better, attitudes were bound to change.

The sharp drop in income for millions of former Soviet citizens was accompanied by a no less painful loss of status. This loss was perhaps even more painful. After all, people could manage to deal with a lower income if this was accompanied by the opening of wonderful new opportunities. Of course, new opportunities did arise, but certainly not for all. An engineer turns into small-time vendor. A translator specializing in the study of chivalrous tales from the Middle Ages becomes a salesman of imported sausages (ironically from the same region in France of his favorite heroic knights). Tens of thousands of military personnel were demobilized and turned out incapable of functioning in ordinary civilian life. All of this could not but cause depression and longing…

One of the most luminous personal examples of those times was a visit by an exterminator who came to visit my dacha to deal with a rodent problem. The exterminator turned out to be a former major in the Navy, a specialist on protection against chemical weapons. As it turned out, his knowledge and skills came in handy for poisoning rodents.

A society that has undergone such stress will undoubtedly reassess the past. The era of stagnation was soon called a time of stability, with a multitude of attractive and touching elements. People began to collect and preserve old items, and marketing experts have caught on to this trend and begun to turn the familiar Soviet names of factories, clothing and products into fashionable brands, praising them for “that very same taste” and something “familiar since childhood”.

Journalist Olga Balla notes that an entire “industry of reminiscing about the Soviet era” has arisen. The past has been papered with attractive traits. And in most cases they aren’t making things up or even exaggerating. It turns out that those very same things that once caused exasperation and even protest now evoke tender feelings.

This upsurge of nostalgia should not cause surprise. But what is surprising is that this nostalgia has persisted so long and doesn’t appear to be passing. The themes and images that provoked interest a decade ago continue to do so today. Of course, there are two rather attractive and well-known theories explaining this. On the one hand, the elder generation’s nostalgia for the Soviet past is most likely their pining for their own youth. However, such attitudes are no less frequent among the younger generation, which seems particularly inclined to idealize the Soviet era. Just as pining for one’s youth, an absence of information can also give rise to nostalgia. The elder generation at least remembers the long lines, lack of products and other not so attractive attributes of the Soviet era that the younger generation missed out on.

Some say the Soviet nostalgia is a result of state propaganda, as the political stability of the 2000s brings back memories of the Brezhnev era stagnation. But in truth such conclusions can only be reached by those who did not experience life in the Brezhnev era or who have consciously forgotten them. Today’s stability, rocked with scandals and steeped in insatiable consumerism, is not in the least resemble the gray 1970s. And the present elite, regardless of your political views, is in no way similar to the aging leaders that once stood shoulder-to-shoulder on the Mausoleum. And as far as the propaganda is concerned, it is met with success because it plays upon very real attitudes within society.

One can only very conditionally speak about contemporary life as a continuation of the Soviet past. Above all else it seems that this nostalgia stems from a sense of that the past is irretrievable; an understanding that the era has faded into the past forever. You cannot return to that life.

It seems that this pining is not wholly a result of Soviet Nostalgia, but rather something different and more important that relates to today’s reality. We do not so much regret what has been lost as we agonize over what has not been achieved.

Rapid transitions of eras can make society forget about its past. Twenty years following the Revolution, any mention of State Counselors or Merchants of the First Guild sounded no less archaic than the titles of medieval aristocrats sound today. But 20 years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian society continues to live in memories and images of the past. And the reason for this can be found in the present.

Society is aggrieved by the emptiness and vapidity of the new era, the inability of its ideologists to propose a common ideal, the lack of major achievements (such as Soviet citizens had with the victory in WWII, space exploration and even infrastructure achievements, much of which can only be recognized in hindsight).

Soviet nostalgia fills the moral, ideological and cultural vacuum. And it will be overcome only when contemporary Russia succeeds in developing, based on its own experience, new forms of solidarity and can boast of achievements that will unite rather than divide its citizens.

New publications

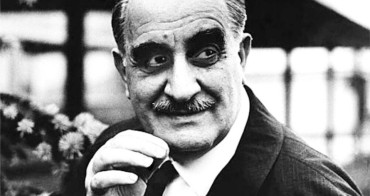

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

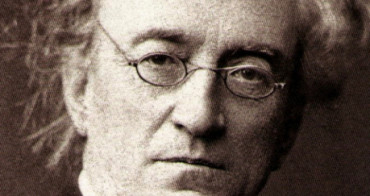

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...