Rare Russian dialect survives untouched in Alaska

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Rare Russian dialect survives untouched in AlaskaRare Russian dialect survives untouched in Alaska

There is a dialect of Russian called Alaskan Russian. It dates back to the second half of the 18th century when Alaska was owned by Russia. The locals had to somehow communicate with Russian manufacturers and merchants. As a result of this communication, a special dialect was born. And although Alaska ceased to be a part of Russia for more than fifty years, the dialect has survived. It is still used in several localities, the main one being the village of Ninilchik on the Kenai Peninsula. But the phenomenon of Alaskan Russian is not only about linguistics and not so much about it. It is about space and time. The territory changed its state affiliation, lost its connection with the Russian culture, and became a full-fledged state of the USA. But the language preserves traces of history in some amazing way.

Ninilchik, Alaska. Photo credit: Jcbutler / ru.wikipedia.org

Language profile

Status: endangered language. Alaskan Russian can be safely called a relict dialect: it is an endangered tool of communication, the language of childhood for the older generation of the local residents of Ninilchik. They prefer to use English as their primary tool of communication.

Language family: a dialect of Russian that belongs to the East Slavic group of the Indo-European language family. Alaskan Russian also had several varieties, at least Ninilchik and Kodiak ones.

Region: several villages on the islands of the Kodiak Archipelago, such as Afognak, and Ninilchik on the Kenai Peninsula. These villages were inhabited by Russian workers and manufacturers who wanted to stay in the "colonies". Russian was also spoken on the Pribilof Islands.

Speakers: 5 native speakers (as of 2020), American and Russian linguists, including Mira Bergelson, professor at the Humanities Department of the NRU HSE, and Andrei Kibrik, professor at Lomonosov Moscow State University and director of the Institute of Linguistic Research of the Russian Academy of Sciences. For the past few years, students of NRU HSE have been working with Alaskan Russian - helping to decipher, digitize, and analyze the materials that the scientists collected during expeditions.

Religious views: Orthodoxy.

Music: Alaskan versions of Russian children's songs with dialect-specific changes. There are also teasing songs with Ninilchik Russian vocabulary.

Creoles, Russian and English languages

Alaska was once a Russian territory: from 1772 to 1867 it was a part of the Russian Empire. The Russian influence can still be felt there. Many geographic sites, such as Baranof Island and Nikolski Island, as well as Shelikof Strait, retain their original names.

According to one version, the first travelers who saw this peninsula were members of the Semyon Dezhnev expedition who sailed through the strait between Eurasia and America in 1648 (later this strait was named the Bering Strait despite the fact that Bering had been there much later). Semyon Dezhnev was a flamboyant person: a seafarer, Yakut ataman, administrator, and fur trader - all in one. He was an explorer and at the same time was unable to write... If a TV series based on his biography was made, some shows like Vikings might be left without an audience.

The Russians began to develop Alaska later, in the mid-18th century. Relations with the locals were not always perfect. There was, of course, a mutually beneficial trade. But clashes also occurred - one of them was the major armed conflict between Russians and Alaska Natives, despite the fact that the total number of deaths on both sides hardly exceeded 300 people.

One of the main trades, as expected, was furs. The Russians engaged indigenous people in this work: the Aleuts, Eskimos, and Athabascans. The workers married local women, and the children born of such marriages gradually formed a special class of creoles.

Creole is not a simple word. For many, it is synonymous with mestizo and mulatto. A dark-skinned сreole is a commonly used phrase. But in fact, creole can be any person born in the colonies: both descendants of Europeans (then the skin is light) and those born of mixed marriages. Alaskan creoles are the latter case.

Alaska could have become a full-fledged Russian colony. Fans of the alternate history genre can let their imaginations run wild and imagine the Red Army soldiers forcing the Bering Strait to defeat the last White Guard stronghold in the Alaskan snow. Then the AlSSR - the Alaskan Soviet Socialist Republic - would appear on the map. Or vice versa: if the White armies held the defense successfully, then Alaska, like Taiwan, would become an independent state with its capital in Novo-Arkhangelsk…

Who knows how events would have unfolded had Alaska not been sold to the United States in 1867. The loss of one and a half million square kilometers can hardly be called a geopolitical tragedy. It is believed that the decision to sell Alaska was imposed on Alexander II by his younger brother, Konstantin Nikolaevich. His logic was quite clear: it is extremely difficult to manage such distant lands, and it is more important to develop ties between regions that are closer to the capital. Most of the proceeds from the transaction were used for this particular purpose - to equip the railroads in Central Russia.

Alaska became American. For several decades it was of no interest to the new authorities, and it maintained contact with Russia through the Russian Orthodox Church until 1917. But in the 1890s there was a gold rush as Americans headed to explore and develop the land. English became the dominant language, and it became a language of instruction in schools 20 years later. Children were punished for using Russian, and after World War II it finally lost its position. The social situation of the creoles under American rule deteriorated, they assimilated and became part of American society.

Photo credit: Rossiyskaya Gazeta

The Devil's dialect and "Sacred Baikal"

Alaskan Russian is the language of descendants of Russian settlers in Alaska who were mostly employees of the Russian-American Company.

The current dialect speakers who live in the village of Ninilchik used to speak Russian at home as children. But they already knew English when they went to school in the 1930s and 1940s. Russian remained the language of their childhood, roots, cultural identity. It was the language of grandparents and parents. Back in 1997, activists from Ninilchik asked Russian linguists - spouses Mira Bergelson and Andrei Kibrik - to help compile a dictionary of the disappearing dialect to preserve it.

“Back then, tribal linguists could be found in many Native American communities where people wanted to recognize their roots. But we were invited to make a dictionary," says Mira.

Mira, Andrei Kibrik, and their children were in the village of Nikolai at the time. The scientists were researching the Upper Kuskokwim language, which was spoken by the Athabascans, Alaskan natives. Local activists helped them to get to the town of Kenai, not far from Ninilchik, and provided lodging and transportation - a huge motorhome where they could live in.

The linguists began interviewing native speakers of Alaskan Russian. They tried to speak to them in English so as not to impose Moscow pronunciation and to prevent possible embarrassment due to rural Russian. Residents had different attitudes toward the study. They were interested but at the same time, there was a lack of trust: why do scientists need information, what do they want to get, what benefits are they going to get out of it?

“Our children helped us to win the informants' favor," recalls Mira. "When the girls sang the romance "Glorious Sea, Sacred Baikal" that their grandmother taught them, it turned out that the elderly people in Ninilchik knew it... There were tears, emotions. The ice was broken.”

Some informants have become close friends of scientists.

“We keep in touch despite the borders,” says Mira. “We call each other on Skype or WhatsApp, congratulate them on holidays directly or through their children and social workers who use social networks.”

If people agree to share their family history, it becomes easier to communicate: most people have warm, pleasant memories of their childhood and family. Bobbie Oskolkoff, who invited Mira Bergelson and Andrei Kibrik to compile a dictionary, even had a poem that helped her to recall Russian vocabulary.

“She recalled her childhood and inserted various Russian words in it. The poem is in English, but about 30% of the words are Russian," explains Mira.

Nevertheless, not everyone is willing to talk about the Russian-speaking past. Russian, like many other Alaska Native languages, was persecuted by the educational system. Children were forbidden to use it in schools: they were beaten, punished, and had their mouths washed with soap for using words in "the devil's dialect". According to Mira Bergelson, the restrictions were not so harsh in Ninilchik, but the Russian speakers were humiliated and made to feel like second-rate people. One native speaker refused to deal with linguists for this very reason: “She wants to feel like a full American and to forget the time when she was "incomplete". She had a trauma.”

Based on interviews with native speakers of the dialect, linguists have been able to describe its phonetic system, develop a script that enables them to record pronunciation features in writing, and create a dictionary of Ninilchik Russian for more than 1,100 entries.

The vocabulary of Ninilchik Russian is diverse, and cannot be considered a part of any traditional, well-established dialects. There are features peculiar to other Russian dialects - probably, they were spoken by Russian settlers with whom the locals were in contact, but there are no systematic correspondences.

After the 1997 expedition, Mira Bergelson and Andrei Kibrik returned to Moscow and did not work on Alaskan Russian for more than a decade. They began working on this subject again after an American linguist had contacted them. He himself didn't speak Russian at all, but his father and aunt spoke the Alaskan dialect very well. The scholar recorded his family's speech by telephone and continued the work of Russian linguists by adding entries to the dictionary. But it turned out that his lack of knowledge of Russian prevented him from doing this: the dictionary was cluttered up.

Mira Bergelson and Andrei Kibrik conducted six more expeditions. They expanded and deepened the dictionary: the printed version of 2017 contains more than 2,500 entries. The electronic version was issued in 2019. It is regularly updated and contains more than 2,600 entries. The scientists have also partially described the grammar of Ninilchik Russian.

Ninilchik, Kodiak and grammar

Such grammatical category as gender is disappearing from the Ninilchik variety of the Alaskan dialect. Native speakers use uncommon prepositional-nominal forms, including in quantity-related combinations. One can frequently hear diminutive forms of words. And the syntax of the Ninilchik variety was affected by English.

Church of the Transfiguration - the Orthodox Church in Ninilchik. Photo credit: Jet Lowe – Library of Congress / ru.wikipedia.org

Evgeny Golovko started studying another variety, Kadiyak Russian, in 2009. He described the lexical system and many other features of this dialect based on field research and interviews. Mira Bergelson and Andrei Kibrick discovered the first written documents in Alaskan Russian 10 years later, which also helped to describe the Kadiyak variety in more detail.

There are no prepositions with cases that indicate direction or location in the speech of its last native speakers.

Cases are sometimes used irregularly; co-occurrence is often violated. Impersonal verbs are also used in unconventional ways in the Kodiak version of Alaskan Russian.

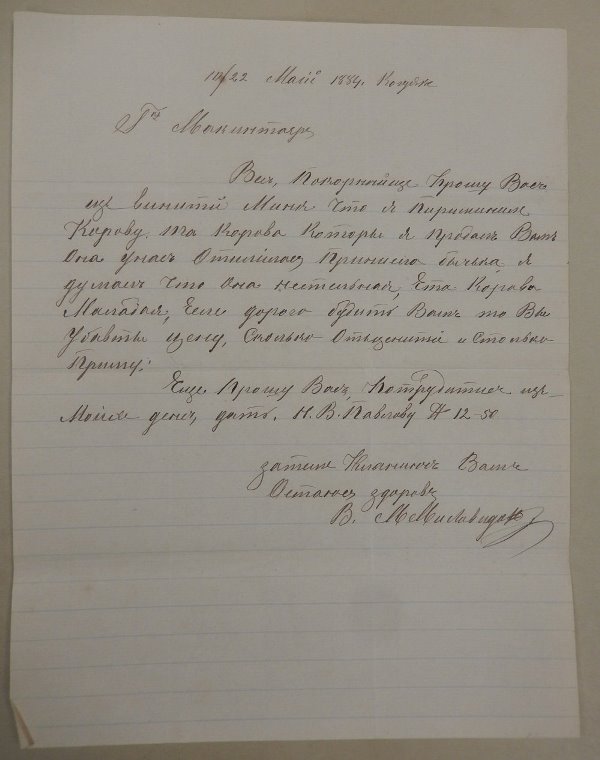

The letters discovered by Mira Bergelson and Andrei Kibrick date back to the period between 1860 and 1910. They disprove the claim that the language of the islanders exists only in the spoken form.

“In a book by Andrei Znamensky, a historian of the Orthodox Church, we read that Orthodoxy in Alaska was mostly promoted by ordinary people-not by priests but a kind of church activists," says Mira. “We saw the famous creole names and realized that since these people had been promoting something, they must have left texts behind, at least letters. They were literate people. We started our research. Kathryn Arndt, an archivist at the Library of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, an expert in Russian American history and an expert on the Russian language, helped us find the materials we needed in the Alaska Commercial Company archives. It had replaced the Russian-American Company (its archives have not survived), and the creoles, native speakers of Alaskan Russian, were hired to work for it. The correspondence was still in Russian for the first 30 years.”

Russian tea and a card game of matrimony

Recent expeditions to Alaska have been rather sociolinguistic. Mira Bergelson and Andrei Kibrik explored the history of culture and how it influenced the preservation or, conversely, the extinction of the Russian language on the island.

“We were struck by the persistence of Russian culture," says Mira. “There is the commitment to Orthodoxy, Russian tea, card games of Durak or matrimony... But language is a fragile thing. Even when it's learned as a first language but not developed further, and the education in school is provided in another language, it will remain at the level of a four- or five-year-old child, and gradually get out of use. The breakdown happens very quickly. Politics, economics affect this as well.”

The word “persistence” can be applicable to Russian-speaking Alaskans, not only to their culture. Mira Bergelson admires the vitality of her Ninilchik friends: they remained committed to their culture and managed to become a part of American life at the same time. And their lives were about hard work: vegetable gardens, hunting, fishing while having families with eight to ten children. They said they never starved although were very poor. However, they felt it when they came to a town only - where money was needed.

These people see Russian colonization differently from the stereotypes - it was the process without arrogant cruelty, although it cannot be called easy. The Russians mixed with the locals and the creoles were born:

“They knew and experienced a lot of things. They're also linguists to a certain extent.”

New publications

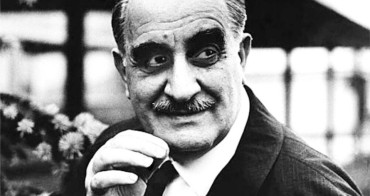

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

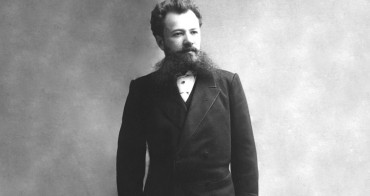

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

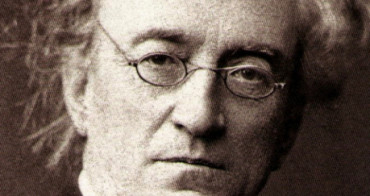

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...