Alexander Alekhine, Russian Chess Legend

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Alexander Alekhine, Russian Chess LegendAlexander Alekhine, Russian Chess Legend

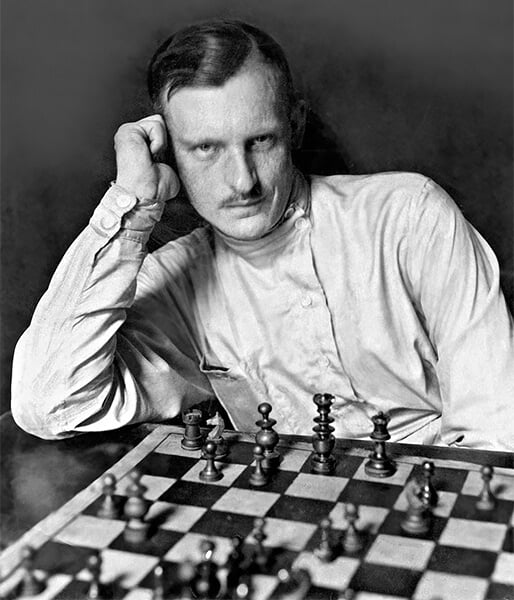

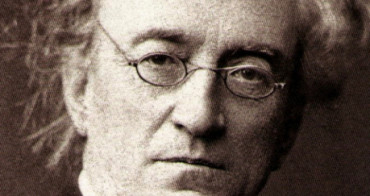

Alexander Alekhine. Photo credit: sports.ru

Alexander Alekhine, one of the greatest chess players of the 20th century and the first Russian World Champion, was born on October 31 (19), 1892. Despite having a brilliant education and being an icon for millions during his years of fame, he died alone, poor, with the chess board in front of him.

"Golden Boy" from Moscow

The would-be king of chess was born into a prosperous Moscow family. His father Alexander Ivanovich was a marshal of the nobility in Voronezh Governorate, a deputy of the State Duma, and eventually attained the rank of Active State Councillor (a civil rank equal to that of Major-General in the Army) by the end of his life. His mother was the daughter of Vasiliy Prokhorov, the owner of the Tryokhgornaya Manufaktura. Anisya Ivanovna played chess and encouraged her sons, the elder Aleksey (who also became a strong chess player) and the younger Alekhander, to play chess.

Alexander was not an infant phenomenon. His talent developed step by step. He learned to play chess at the age of seven. However, he started playing it seriously when he was 12. Alexander was deeply impressed by Harry Pilsbury, a strong grandmaster who came to Russia for a chess tour. The ten-year-old boy participated in his simultaneous exhibition where the American played blindfolded on 22 boards at once. Alexander Alekhine managed to draw his game. Yet, the skill of the overseas celebrity fascinated and inspired him to become a chess maestro as well.

Alexander and his older brother Aleksey started to participate in a correspondence play, an analog of the network tournaments a century ago. He had sufficient time and opportunities for that as the boy studied in a private Moscow grammar school, and the teachers tolerated the new chess player's academic failures. By the way, according to the memoirs of Mr. Alekhine's classmate and friend Pavel Popov, he was a typical person of a humanities bent. He was quite good at languages, and he wrote essays well, however, he had a hard time with mathematics.

"Speaking of skills, Alexander Alekhine had the worst performance in mathematics," Mr. Popov wrote. "This is a paradox as chess talent is believed to be associated with mathematical abilities. Alexander's math results were so poor that he had to seek the help of the tutor. On the final exam, he got a D as he failed to solve the trigonometry problems and messed it up badly. He was allowed to take the oral exams conditionally. He got a B in trigonometry on the oral exam. So, the average grade was C.”

Participation in correspondence tournaments boosted the young chess player's talent. First, he helped his older brother to analyze games. It didn't take long before he began to play in tournaments independently.

In 1907, Alexander Alekhine, a grammar school student, took part in an amateur tournament at the Moscow Chess Group for the first time. It was then that a historic meeting took place: the 14-year-old Alexander met Mikhail Chigorin, the first Russian participant in a world championship match.

Mr. Chigorin was an iconic personality among Russian chess players. He had two matches for the world title with the world champion Wilhelm Steinitz and developed a so-called "romantic" style of play. Later, Mr. Alekhine adopted a similar style of play and managed to become a world champion, which Mr. Chigorin had failed to achieve.

The young master

The first place at the 1909 All-Russian Amateur Tournament in memory of Mr. Chigorin was the first real success for the young chess player. His reward included an expensive vase made by the Imperial Porcelain Factory and the honorary title of "Maestro".

At the same time, Mr. Alekhine continued his studies. Having finished the grammar school in 1911, he entered the St. Petersburg Imperial School of Jurisprudence. However, jurisprudence was not of particular interest to the young man. Chess remained his primary activity.

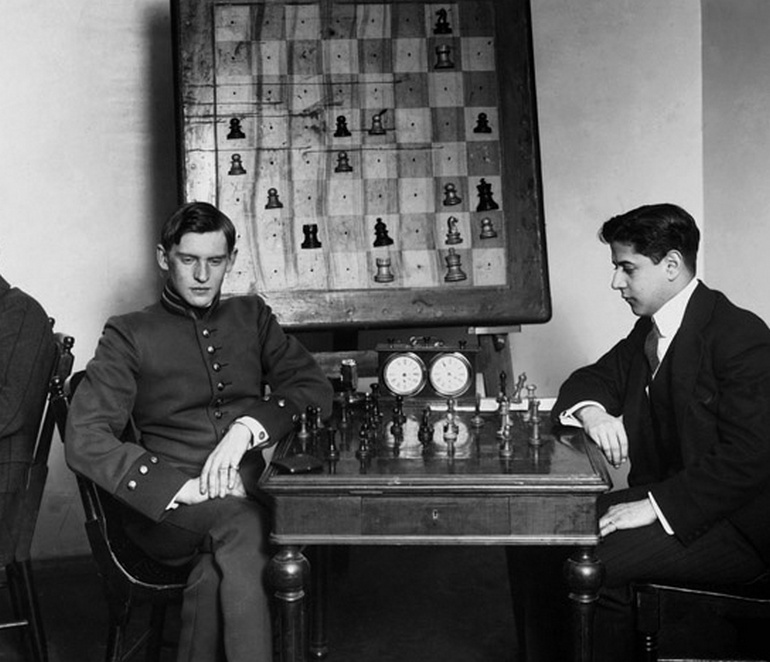

Mr. Alekhine, a student at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Alexander moved to the capital and successfully participated in several foreign competitions. In 1914 he qualified for a prestigious tournament in St. Petersburg. It was attended by virtually the entire chess elite of the time. Mr. Alekhine performed more than well in that tournament. He was outperformed only by Emanuel Lasker, the reigning world champion, and José Raúl Capablanca, a rising chess star.

Back then Alexander Alekhine realized that he was strong enough to compete for the world title. So he started studying... Capablanca's games. His surprised chess club colleagues asked him why he ignored the games of the reigning champion Emanuel Lasker. Mr. Alekhine used to reply that Mr. Capablanca would undoubtedly become the world champion soon. So it happened.

In May 1914 Mr. Alekhine completed his studies to become a lawyer. He was promoted to the rank of titular counselor and appointed to the Ministry of Justice. However, he was only technically registered there, as permitted by his superiors. His entire time was devoted to participating in chess tournaments.

War, threat of execution, emigration

It may seem that the young chess player's life was finally settled: tournaments, tournaments again, and the coveted chess crown somewhere ahead. Unfortunately, life took its toll and the hard times approached.

Mr. Alekhine in the white uniform of the School of Jurisprudence participates in a tournament in Stockholm, 1912. Photo credit: chesspro.ru

In the summer of 1914, Mr. Alekhine was successfully performing at a tournament in Mannheim, Germany. Meanwhile, the World War broke out. The organizers decided to discontinue the tournament. Mr. Alekhine was awarded first place and paid the promised remuneration for the victory. However, just after that, he and other participants from Russia ended up... in a German prison. The German authorities took such a harsh action based on one photo of Mr. Alekhine playing chess in the uniform of a law student, and it had been mistaken for a Russian officer's uniform.

Alexander Alekhine recalled that chess players used to play blindfold all day long while in prison. Nevertheless, the mistake was soon reversed, and Mr. Alekhine was released. He returned to his homeland and continued to participate in tournaments. All his earnings were used to help Russian chess players imprisoned in Germany.

In 1916 Mr. Alekhine went off to war as a volunteer fighter. He headed a Red Cross flying squad at the Galician front. Mr. Alekhine served selflessly. He used to carry the wounded from the battlefield by himself. As a result, he got two shell shocks and then returned to Moscow. Alexander Alekhine was awarded two St. George medals for his courage and nominated for the Order of St. Stanislaus, 3rd degree with swords, which he was not able to receive.

The overthrow of the monarchy in Russia followed by the October Revolution later was another twist. The revolution stripped Mr. Alekhine of his nobility and wealth. His only possession left was chess.

Mr. Alekhine didn't have any particular political position. When the Bolsheviks came to power, he found himself between two fires.

In 1918 he moved to Odessa. However, the city was soon occupied by the Red Army. The Odessa Cheka accused Mr. Alekhine of conspiracy with the White Army, and he was sentenced to execution by firing squad. Fortunately, there was a high-ranking chess enthusiast among the Red commanders who knew who Mr. Alekhine was. The chess player was released and even employed by the Odessa Executive Committee. Nevertheless, soon the White Army began its offensive, and the chess player went back to Moscow through Kharkov where he suffered typhoid fever.

His further life can be described as phantasmagoria. While in Moscow, Mr. Alekhine got a job... in the police as a tracing investigator. At the same time, he was invited to work for the Comintern as an interpreter.

As the tension of the Civil War declined, chess life was revived in the capital. In 1920 Mr. Alekhine won the first All-Russian Chess Olympiad (later it was recognized as the first USSR Chess Championship).

In 1921 Mr. Alekhine got married to Annelise Rüegg, a representative of the Swiss Social Democrats in the Comintern. He and his wife left for Europe, where Mr. Alekhine focused on chess life. His goal was to become a world champion, so he actively participated in chess tournaments.

Photo credit: sports.ru

Match with Capablanca. Triumph

His way to the chess crown was obstructed by the London Protocol stipulating the procedure for challenging the reigning champion to a title match. The reigning champion, José Raúl Capablanca from Cuba, would only agree to play subject to the above Protocol. Its conditions were tough: the challenger had to raise $10,000, a rather significant sum for those times, to establish a prize fund and cover all the expenses associated with the match.

The London Protocol was an impassable barrier to the title of World Champion for many strong chess players. As Mr. Alekhine was stripped of all his assets by the revolution, he certainly had no such money. However, he was not discouraged.

He organized record-breaking blind matches in New York (26 games) and Paris (27 games). He played a simultaneous exhibition from an airplane, and organized chess battles where actors were used as pieces. He acted almost like a showman, all to collect the required amount. Finally, the efforts of the Russian chess player were rewarded. In 1927 the Argentine government promised to allocate funds and hold a match in Buenos Aires.

The chess players who had to meet in the "match of the century" were opposites in many respects. Mr. Capablanca was the public's favorite. He had a reputation as a gentleman, a playboy, and a brilliant chess genius with great intuition. He was referred to as a "thinking machine." As for Mr. Alekhine, he was known as an unsociable person who also abused alcohol. Nevertheless, his efforts in preparing for the matches were recognized by all. The experts generally agreed that Mr. Capablanca, who had held the champion's title for six years by then, was the undisputed favorite and would easily defeat the Russian chess player. Furthermore, the results of their head-to-head meetings weren't favorable to Mr. Alekhine. The Cuban player had previously defeated his Russian partner three times.

The long-awaited match took place in Buenos Aires in the fall of 1927. It became a real sensation. Chess enthusiasts in every corner of the world, including Soviet Russia, followed this event with fascination.

Jose Raul Capablanca vs Alexander Alekhine. St. Petersburg, 1914. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Mr. Alekhine worked hard in preparation for the meeting studying his opponent's games in detail. This meticulousness helped the Russian chess player. A total of 34 games were played over two months. The match was not easy for Mr. Alekhine: he even ended up in hospital during the meeting. He had a jaw inflammation and lost six teeth.

Nevertheless Mr. Alekhine won six games while the tournament should have been played to seven victories. Eventually, Mr. Capablanca surrendered and did not show up to play the last game. Alexander Alekhine was declared the 4th World Champion.

It was a pure triumph! The exalted crowd carried the Russian chess player in reverence through the streets of the Argentine capital. Mr. Alekhine received a warm welcome in Europe as well. Thus, a new chess star was born.

Later, Mr. Capablanca requested a return match but on his own terms. Mr. Alekhine replied that he would play under the London Protocol only, i.e. under the same conditions that he had met to win the title, including a fee of 10,000 dollars. As a result, the return match didn't take place, and the two great chess players became almost enemies from that time onwards.

Breakup with Russia. Emigration to France

All Russian people on both sides of the border celebrated Mr. Alekhine's victory. The chess clubs of Paris, Moscow, and St. Petersburg rejoiced as well. However, Mr. Alekhine's statement cast a long shadow on his bond with Soviet Russia. The morning after Mr. Alekhine was honored in Paris, the newspapers' headlines claimed, "The world champion wished for the legend of the undefeatable Bolsheviks to disappear, just as the myth of the undefeatable Capablanca had." No one knows whether Mr. Alekhine really said those words or whether they were made up by the newspapers but Moscow resented the new champion gravely, and soon he was officially declared an "enemy of the Soviet state".

Mr. Alekhine made this breakup formalized: he acquired French citizenship and headed the French national team at the following Chess Olympiads.

That was the period of Alexander Alekhine's undisputed leadership in chess. In 1929 he defended the champion's title in a match against the Soviet master Efim Bogoljubow. In 1930, he triumphed at the prestigious tournament in San Remo where he won thirteen out of fifteen games. In 1932, he embarked on a big round-the-world chess tour and visited more than fifteen countries (the USA, Mexico, Japan, China, the Philippines, Indonesia, New Zealand, etc.). Over that time, he played about 1300 games with 1161 wins and only 65 losses. Such a phenomenal result! Having returned, in 1934, he once again defended the champion's title in a match against Mr. Bogoljubow.

Match against Max Euwe

In the mid-1930s Alexander Alekhine seemed to grow weary of not having any decent rivals. He divorced Nadezhda Vasilyeva, his faithful companion for 10 years. Then he married the Anglo-American chess player Grace Wishaar, who was rich but much older than him.

The year 1935 was marked by the appearance of a new contender for the chess crown. It was Max Euwe, a modest mathematics teacher from the Netherlands. Before the match, the odds were almost the same as those before the match with Mr. Capablanca. However, this time, Mr. Alekhine was considered the obvious favorite.

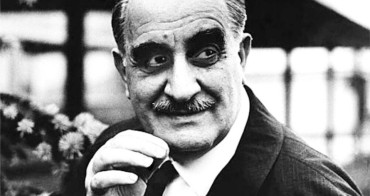

Chess game with Max Euwe. Photo credit: sports.ru

It was a closely contested match. the outcome was decided in the last thirtieth game. Mr. Alekhine needed to win it but was unable to do so. He lost with a score of 14.5: 15.5. Many contemporaries agreed that the Russian chess player's excessive self-confidence and alcohol consumption during the match had interrupted his victory.

Nevertheless, Alexander Alekhine would not have been a great champion if he had given up that easily. He managed to focus and defeated Mr. Euwe in a return match in 1937. The score was 15.5: 9.5. The Dutchman had lost a total of ten games!

The champion's fall

During the years prior to the war, Mr. Alekhine retained his reputation as the strongest player. Nevertheless, a new generation of chess players had grown up by that time, and the strongest of them was Mikhail Botvinnik, the Soviet grandmaster. A match between Mr. Alekhine and Mr. Botvinnik for the world champion title was scheduled for 1939. However, the war interfered with the plans once again.

When World War II broke out, Mr. Alekhine joined the French army as a volunteer and served there as an interpreter. Once France was occupied, Alexander Alekhine moved to the south of the country. The Nazis actively used well-known people in their propaganda and engaged Mr. Alekhine as well. A story of his cooperation with the Germans seriously jeopardized Mr. Alekhine's reputation in the chess community.

Alexander Alekhine participated in tournaments held by the Third Reich authorities. A series of anti-Semitic articles bearing his name were published in the German-language newspaper Pariser Zeitung in 1941. They had a common title "Jewish and Aryan Chess" and became a more serious accusation against him.

After the war, Mr. Alekhine tried to justify himself. He claimed that he had to cooperate with the Nazis to guarantee the safety of his interned wife with British nationality and Jewish roots. He also said that he had only provided an analysis of the games for those disgraceful articles, and all the anti-Semitic remarks had been made by the German editor of the newspaper only.

In 1943 Mr. Alekhine suffered severe scarlet fever. Soon he relocated to Spain. His life was lonely and modest there. He hardly socialized with anyone, yet participated in second-rate tournaments and was even compelled to give private lessons.

The year 1945 saw the revival of chess life in Europe. Yet, the world champion was boycotted. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union offered a helping hand to Mr. Alekhine. The USSR announced that it was still interested in holding a match between Alexander Alekhine and Mikhail Botvinnik, as the latter had insisted on it. In February of 1946, Mr. Alekhine gave his consent to the match, and the International Chess Federation (FIDE) approved it. However, the following morning brought the news of Alexander Alekhine's death. He was found dressed in his home. There was a chessboard with a game started in front of him…

There were speculations that he had been killed by either the Soviets or one of the Western intelligence agencies. However, in fact, Alexander Alekhine died of asphyxia caused by food entering the respiratory passage... The fourth world champion was buried in Estoril. In 1956, his widow requested him to be reburied in Paris, having rejected the Soviets' proposal to do that in Moscow.

Alexander Alekhine as a person

Mr. Alekhine had a complex personality. He was remembered as a man of great erudition and a charismatic conversationalist who spoke six languages. At the same time, there are those who describe him as a rather cynical person.

There was much written about Mr. Alekhine's addiction to alcohol, especially from the 1930s onwards. However, it is known that he did not drink alcohol and kept regular hours before major tournaments, including a match against Mr. Capablanca and a return match against Mr. Euwe, and did not drink alcohol at all.

He was married several times. Still, family was not the most important thing in his life. He had two children from different women, Valentina and Alexander. However, Mr. Alekhine was not personally involved in their upbringing.

Mr. Alekhine was known to have a great fondness for cats. His Siamese cat Chess was always present at competitions as a mascot.

With Chess the cat. Photo credit: chesswood.ru

… and as a chess player

Alexander Alekhine passed away at the age of 53. He was still the reigning world champion and the only chess player to die undefeated. He remains one of the greatest chess players of the 20th century.

Mr. Alekhine stood out for his vivid attacking style and deep theoretical elaboration of positions. His name has been given to a number of combinations, including the Alekhine Defense. He was recognized for his skills in creating complex and spectacular multi-pass combinations and was awarded Brilliancy Prizes more than once.

The fourth world champion was also a skilled blindfold performer. He is even referred to as the greatest master of this genre. He set several records in terms of the number of opponents in simultaneous blindfold exhibitions.

In 1970, the participants of the Match of the Century (USSR vs. the rest of the world) were asked to name the best chess player of all time. Most of them mentioned Alexander Alekhine. According to statistics, Mr. Alekhine ranks first among all world champions by the percentage of games won - 58%.

He contributed to the popularization of the ancient game more than anyone else by traveling all over the world and playing countless games. Alexander Alekhine believed in the inexhaustible potential of chess and its creativity. "Chess for me is not a game but rather an art. Yes, I regard chess as an art and assume all the responsibilities it imposes on its adherents," he said.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

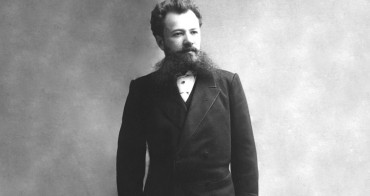

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...