Normal Russian Languages

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Normal Russian LanguagesNormal Russian Languages

The conference Russian Language in a Multicultural World recent took place in the Crimea and was attended by a very respectable and diverse group of professionals. We spoke with one of the key speakers at the event, Yuri Prokhorov, rector of the Pushkin State Institute of Russian Language, about whether we should expect a regionalization of the Russian language and whether efforts should be made to preserve the purity of the language.

– At the conference, you spoke about a widening gap between the Russian language and the Russian cognitive base. If I understand you correctly, you indicate that this is characteristic of those who use the Russian language outside the context of modern Russian culture, that is, for foreigners who use Russian?

– No, we are talking about people living in other countries but for whom Russian is their native language. However, the context in which they develop their communication is different – socially and culturally different. So it is natural that I, living in this culture, formulate things a certain way, and they in a different way, but nonetheless in the Russian language. This is a natural occurrence.

All of our communication has three components. For example, here I am today in Yalta and I say: “It’s really warm here.” But my old pal Rafael Gusman, who flew in from Spain where it is 35 degrees Celsius, tells me: “Thank God it’s cool here!” We are speaking in the same Russian language but with different perceptions of reality. I know something about this reality and I know how to speak about it. There is the reality, the text (my knowledge of it), and then the discourse (what I bring to the conversation). And, like a hologram, this 3-D reality is always in motion.

For example, if you approach someone with a question: “Could you please tell me…?” And in response you hear: “What’s up?” This discourse colors your approach to the conversation. A text immediately arises in our consciousness – we understand where this construction of speech comes from and we begin to perceive the person differently. Communication is cognitively pragmatic. As soon as our perception of the cognitive base upon which this communication is to take place changes, then we are faced with the pragmatic choice: whether to engaging in conversation or not, how to engage, in what language, etc.

– Professor Alexander Rudakov of National University spoke at the conference about the idea that we can say there are different “worlds” of the Russian language: one in Russia, a different one in Ukraine, a third in Kazakhstan, and so on. Do you agree with this approach?

– Yes, I do. Because the world in which a Russian speaker grows up is different in different regions. For example, someone can say, “Tomorrow is our favorite holiday Kurban Bairam.” But then I will need some sort of explanation: what is this celebration, what are its traditions, how is it celebrated, etc. The same kinds of questions could arise with others regarding our holidays, for example, do we take the eighth of March off. We have our own worldview, and this is related to the social reality we live in.

– This regional differentiation – is this normal? Should it be accepted or do we need to fight for the purity of the Russian language?

– You can’t fight this, just as you can’t fight reality. It’s pointless.

– In that case, after a certain amount of time we will see separate dictionaries for Ukrainian Russian, Russian Russian, and so on, just as we now see modern British English dictionaries and American English dictionaries…

– Don’t we hear that have of the people in Ukraine speak in Ukrainian Russian, from the phonetics to the structure? Yes, we hear it.

– Perhaps, to the contrary, we need to “impress in the masses” cultured speech, rather than give up on this? After all, for hundreds of years the pure Russian was spoken in Kiev. Otherwise we will be forced to recognize the validity of Surzhyk…

– Yes, the local intelligentsia practically all spoke in pure Russian. But why was this? Because they lived in the same reality. Why do we recognize that there is American English, British, even Australian and Indian variations, but think that this isn’t possible with Russian. We no longer have the united community of Soviet people. We have independent states and the Russian-language speakers of these countries have a worldview that is in one way or another unique. For example, I can’t call the Ukrainian parliament the Supreme Council or the Duma. It’s the Rada, even though such a word does not exist in the Russian language. And these instances are quite common. We live in a new reality – politically and socially – and the issue of Surzhyk isn’t that black and white. This needs some careful consideration.

We often hear, “We are losing the language of Pushkin.” But do we really read and understand Evgeny Onegin just as Pushkin wrote it? Commentary on Evgeny Onegin is larger than the poem itself. Right now we read it in our own manner, but we haven’t lost Pushkin’s language, because we can read him in the Russian language. If we really did continue to speak in the language of those days, it would indicate that life came to a halt a long time ago.

Language not only facilitates the translation of culture, it provides something more important: my existence in the “here and now”. If something goes not quite right, my “mail” might “malfunction”, and then I might try to fix it with the help of a “mouse”, and so on. And that’s quite normal.

And have you read Pushkin’s letter to Natalya Nikolaevna? In this letter in 1932 he writes the ingenious phrase: “A ‘v

New publications

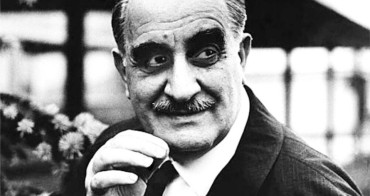

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

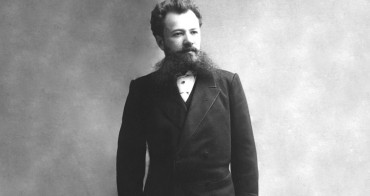

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

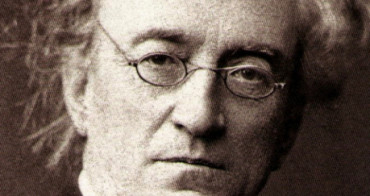

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...